Research

CloseSystem analysis

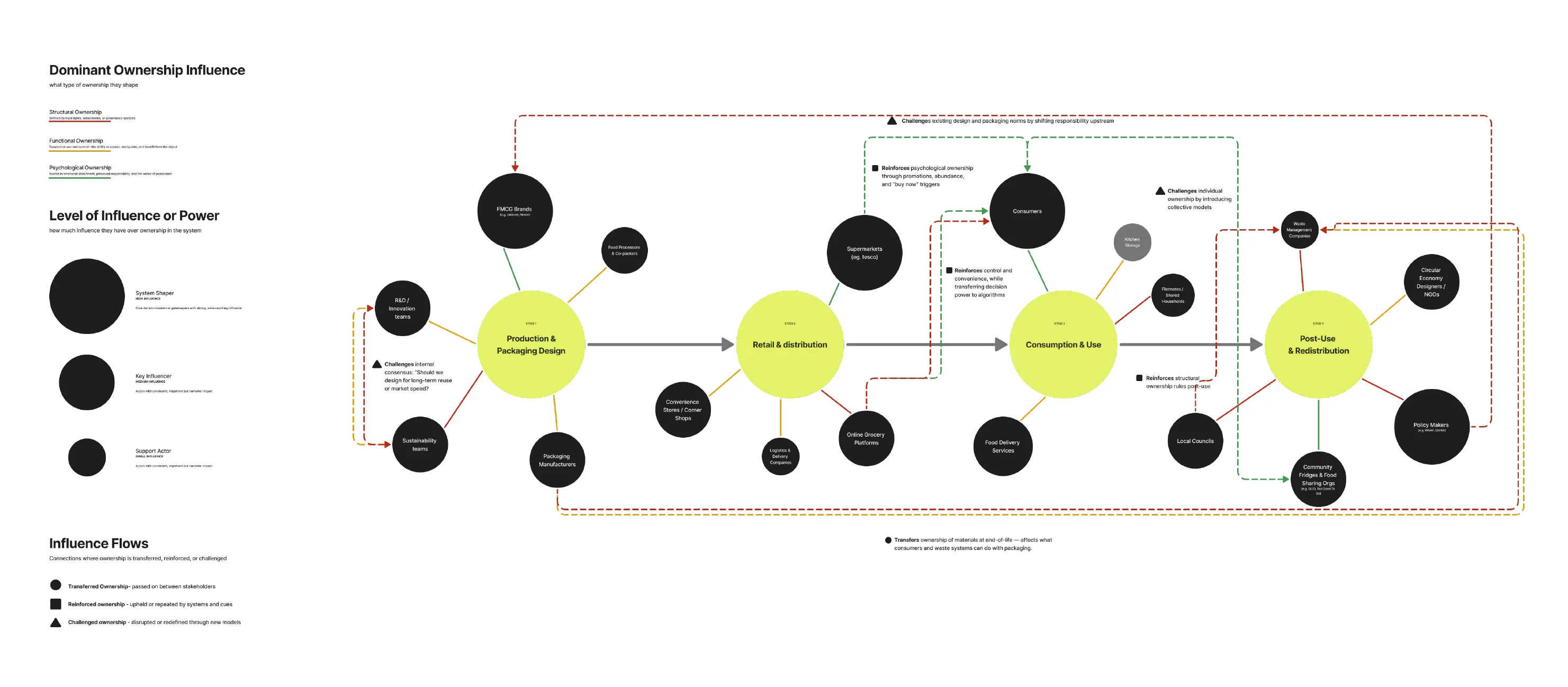

Ownership lifecycle

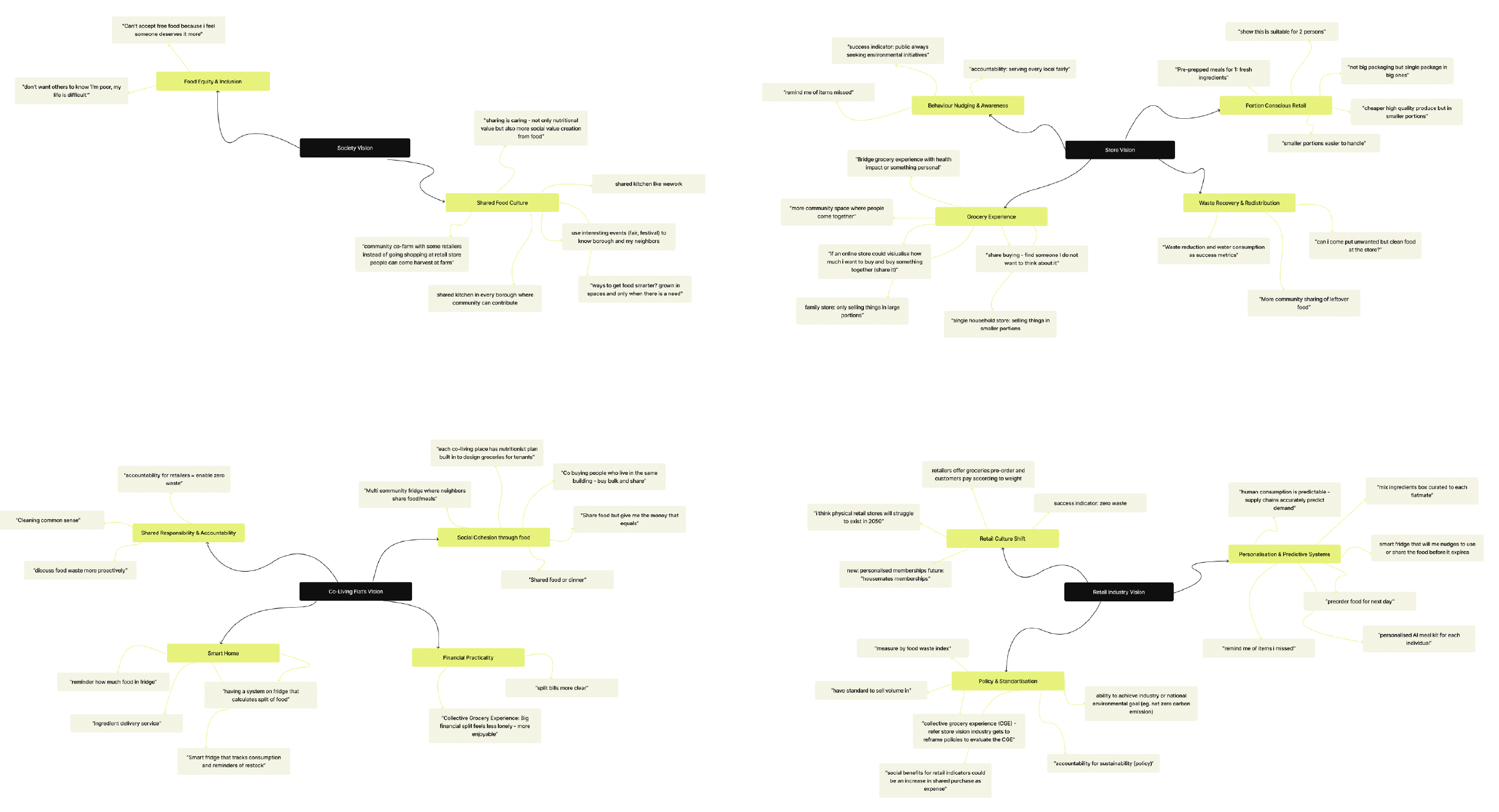

We created a detailed system map to visualise how ownership is produced, distributed, and transformed across the lifecycle of packaged food. The map identifies key stakeholder groups, from producers and retailers to consumers, community fridges, and policymakers, and locates them within four lifecycle stages: 1. Production & Packaging Design, 2. Retail & Distribution, 3. Consumption & Use, 4. Post-Use & Redistribution. We analysed their types of ownership influence (structural, individual, psychological), relative power, and how ownership is transferred, institutionalised, or challenged through systemic flows. We wanted to move beyond viewing ownership as an individual attitude, and instead reveal it as a systemic condition shaped by roles, rules, and relationships. By mapping how ownership flows and transforms between stakeholders, we could identify critical leverage points for design interventions. This approach helps surface the complexity of shared responsibility in FMCG systems, highlighting how interventions must align with existing power structures and enable collaborative forms of ownership to scale.

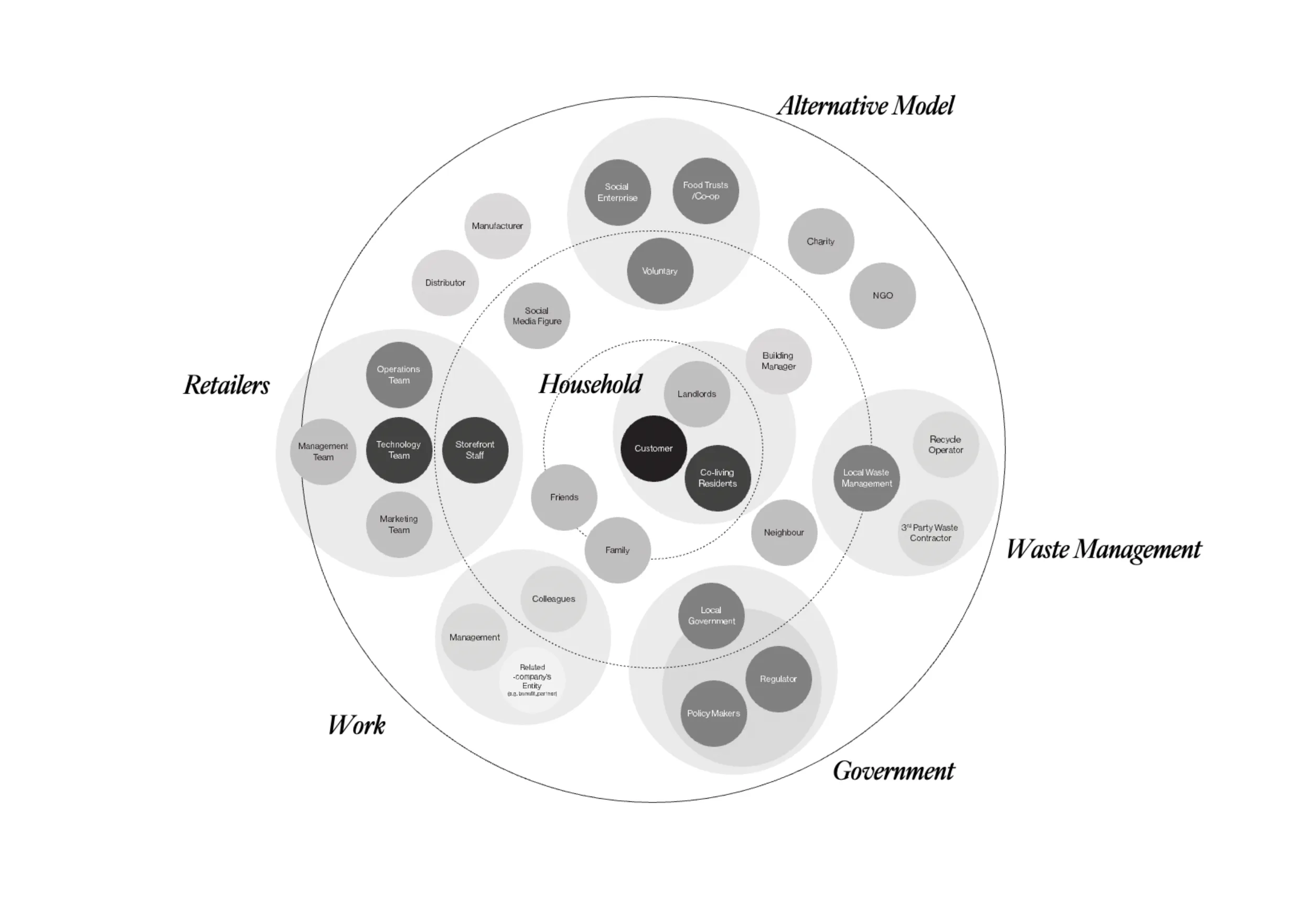

Stakeholder Map

We created a stakeholder ecology map that positions the customer and household within a broader ecosystem of actors influencing food ownership practices. This included retailers (management, marketing, operations, storefront staff), waste management entities, government regulators, landlords, co-living residents, social enterprises, NGOs, and voluntary initiatives. We used concentric layers to illustrate proximity and relational influence on the customer’s experience of ownership. By visualising this ecology, we could see how retailers, policy-makers, local government, and alternative models all play roles in enabling or constraining shared responsibility. This approach supported a more holistic, systemic framing of our design challenge, emphasising that shifting ownership models requires cross-sector collaboration, not just consumer behaviour change.

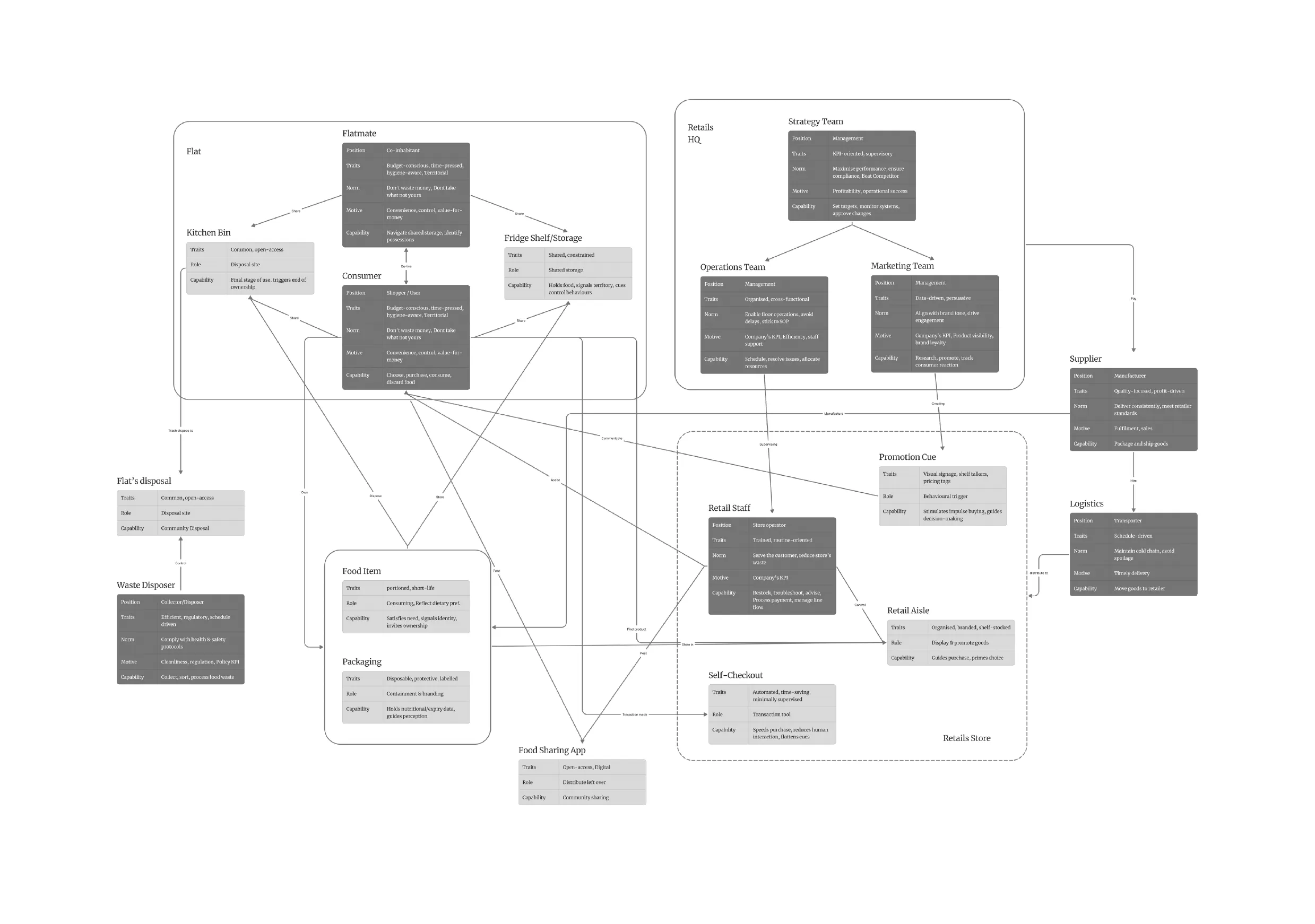

Behaviour Setting Map

To make sense of how these systems shape everyday behaviour, we applied Behaviour Setting Theory (Barker, 1968). This allowed us to map the physical, social, and normative environments in which food ownership behaviours emerge.

We detailed:

- Roles (consumer, flatmate, retail staff, bin user)

- Norms (self-monitoring, deal-seeking, “it’s mine if I paid for it”)

- Motives (convenience, value, trust)

- Artefacts (fridge, loyalty cards, checkout zones, shared shelves)

Rather than viewing ownership as a fixed or personal mindset, we revealed it as:

A distributed and dynamic process, negotiated through routines, roles, and shared settings, from store to kitchen to bin.

By mapping these behaviour settings, we surfaced how ownership becomes:

- Fragmented in shared housing

- Negotiated in pricing and promotions

- Institutionalised in retail structures and policies

This approach revealed hidden constraints and overlooked opportunities for intervention, howing us where the system actively resists more collaborative, circular models of consumption.

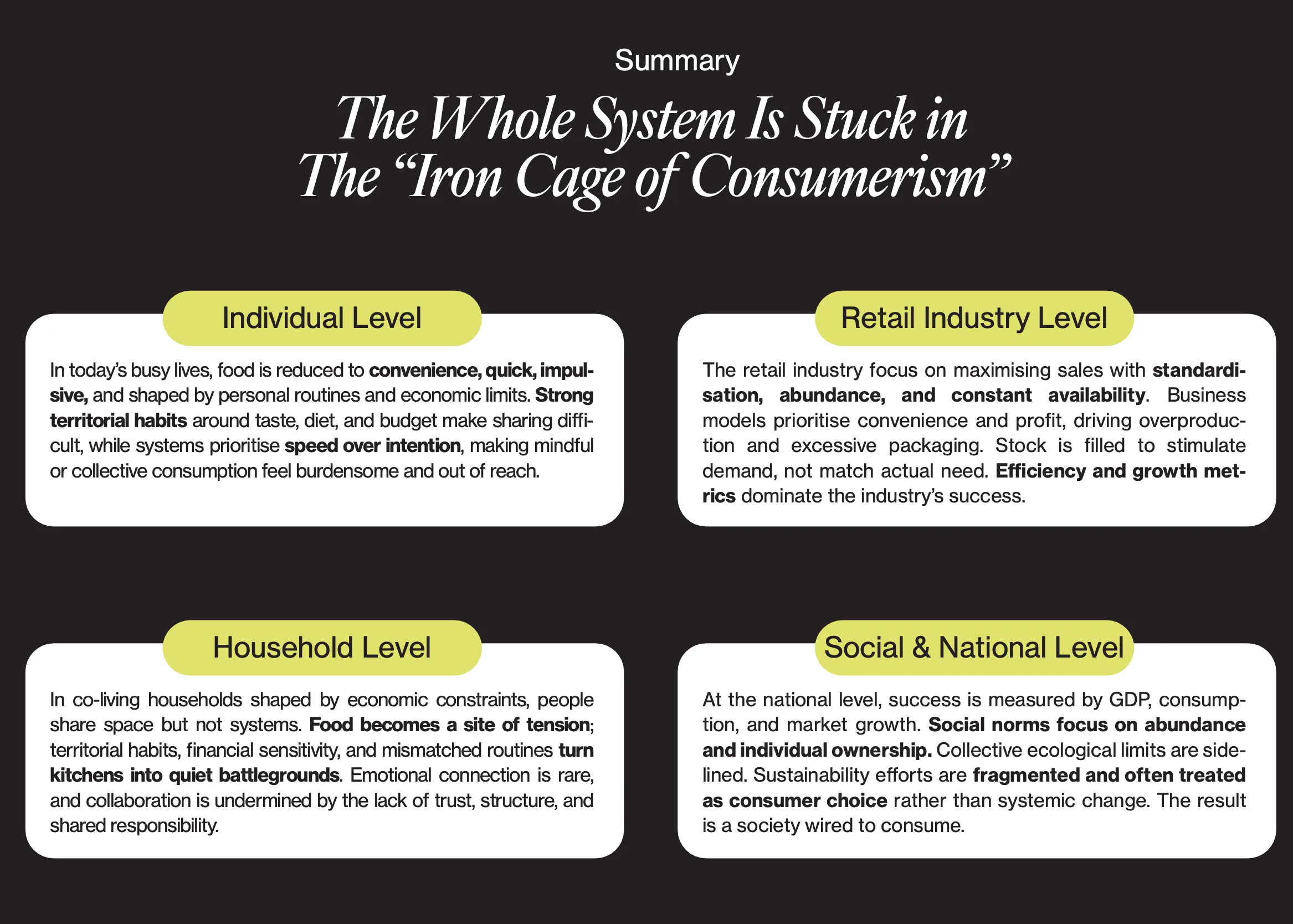

Through our combined analysis, stakeholder mapping, system mapping, and behaviour setting theory, we uncovered a core insight:

The system is not neutral. It actively shapes what people buy, how they store food, when they share (or don’t), and how waste is normalised.

From promotional pricing structures to fridge design, from loyalty cards to pack sizes, we saw how design choices across the food retail system profoundly shape individual decisions, mindsets, and assumptions about ownership.

What often appears as “personal behaviour” is in fact the outcome of layered social norms, physical constraints, and institutional signals.

This shifted our design question from:

“How do we get people to waste less?”

to

“How might we redesign the system so that wasting less becomes easier, more natural, and even socially reinforced?”

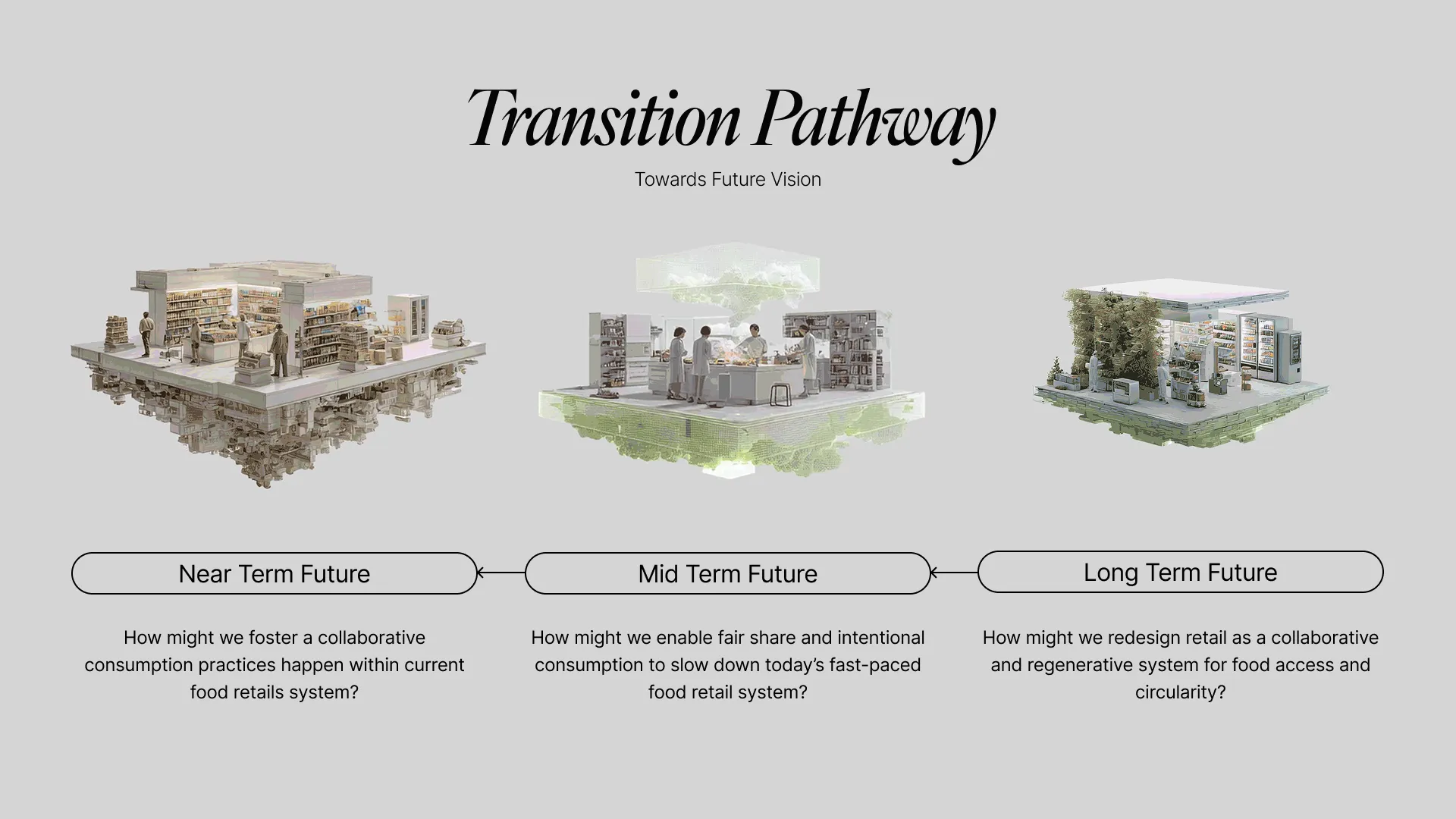

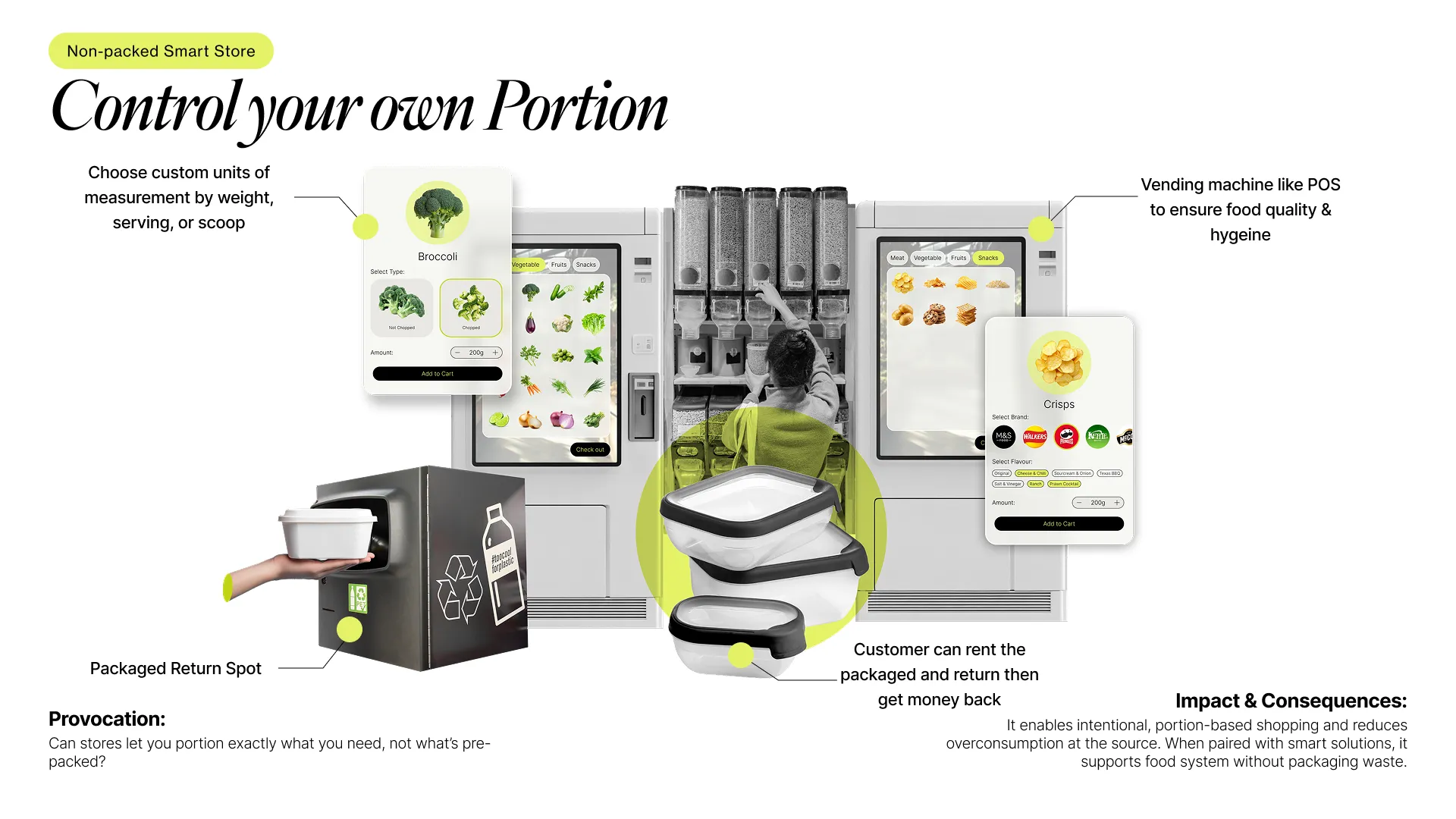

This systems-first mindset informed our next steps: designing speculative futures and transition interventions that challenge current defaults and propose new infrastructures for food ownership and retail.

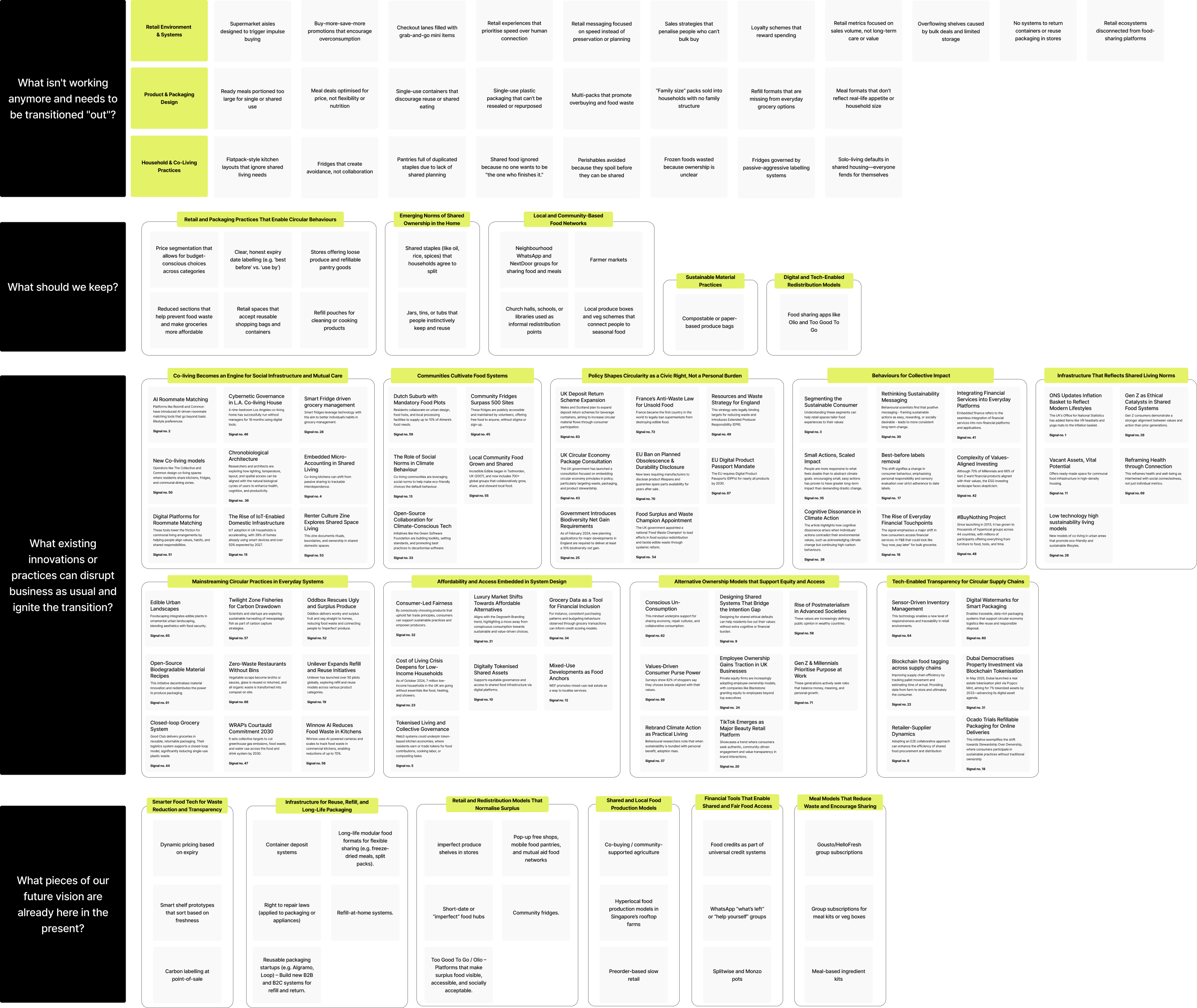

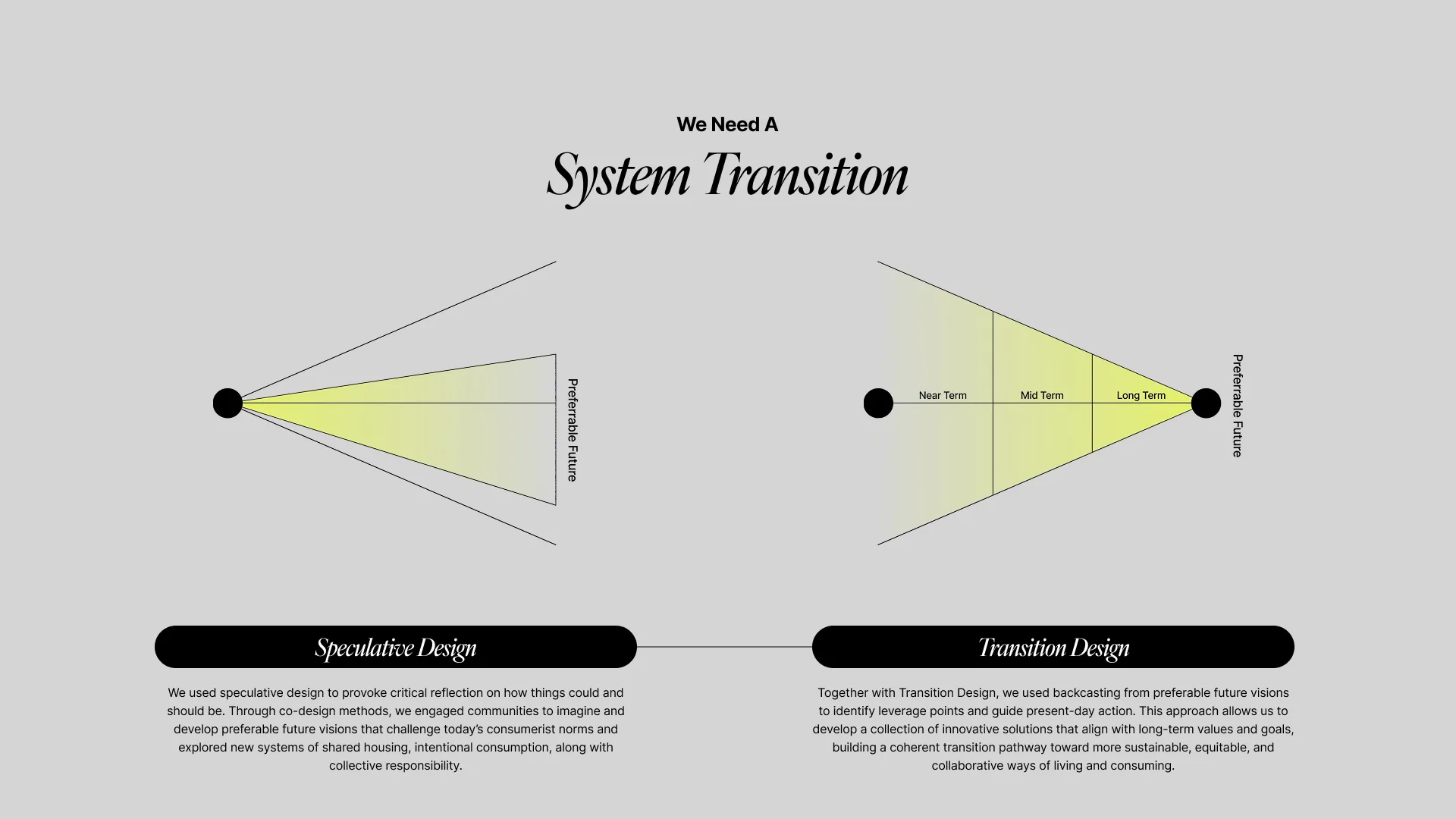

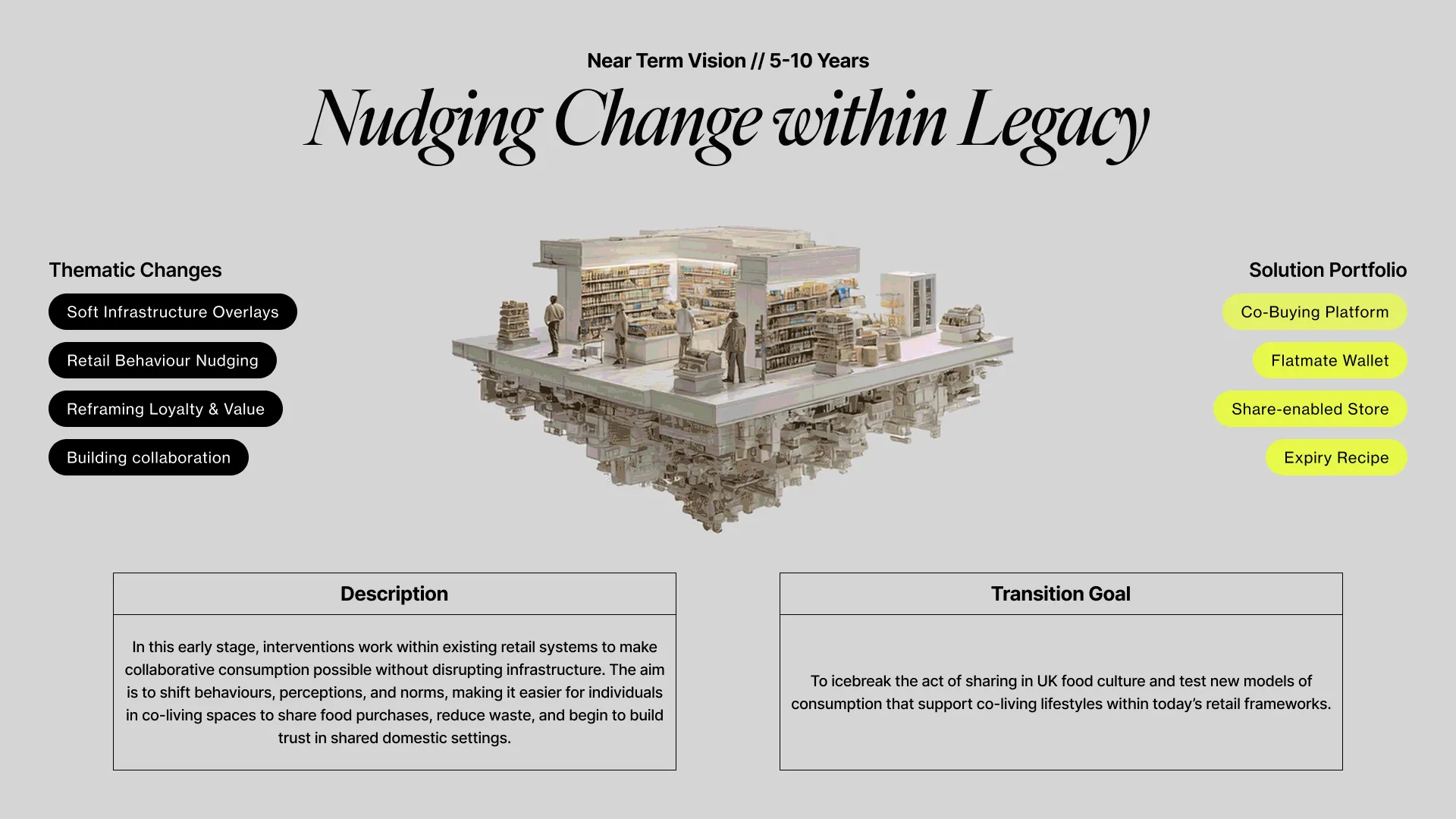

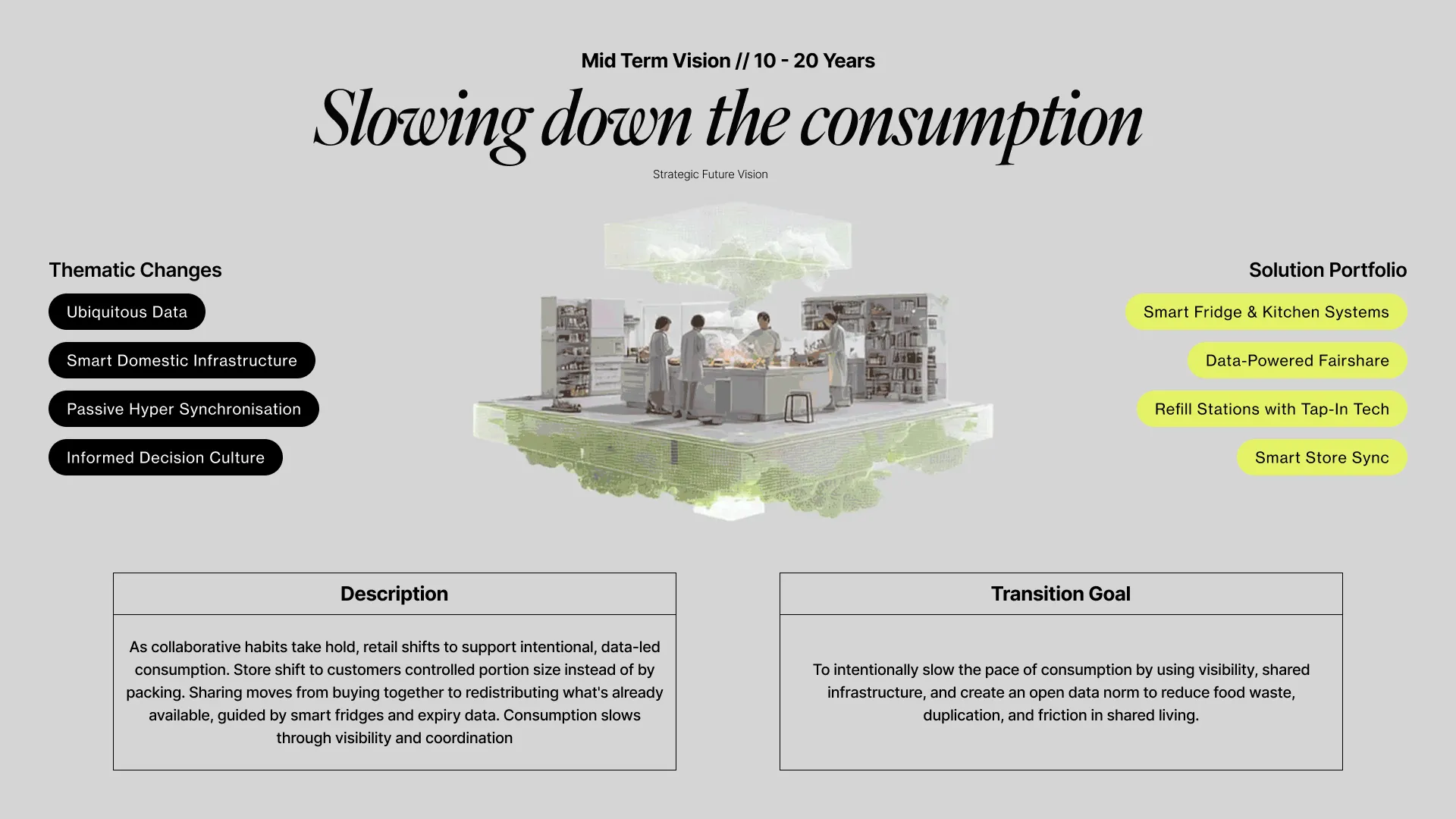

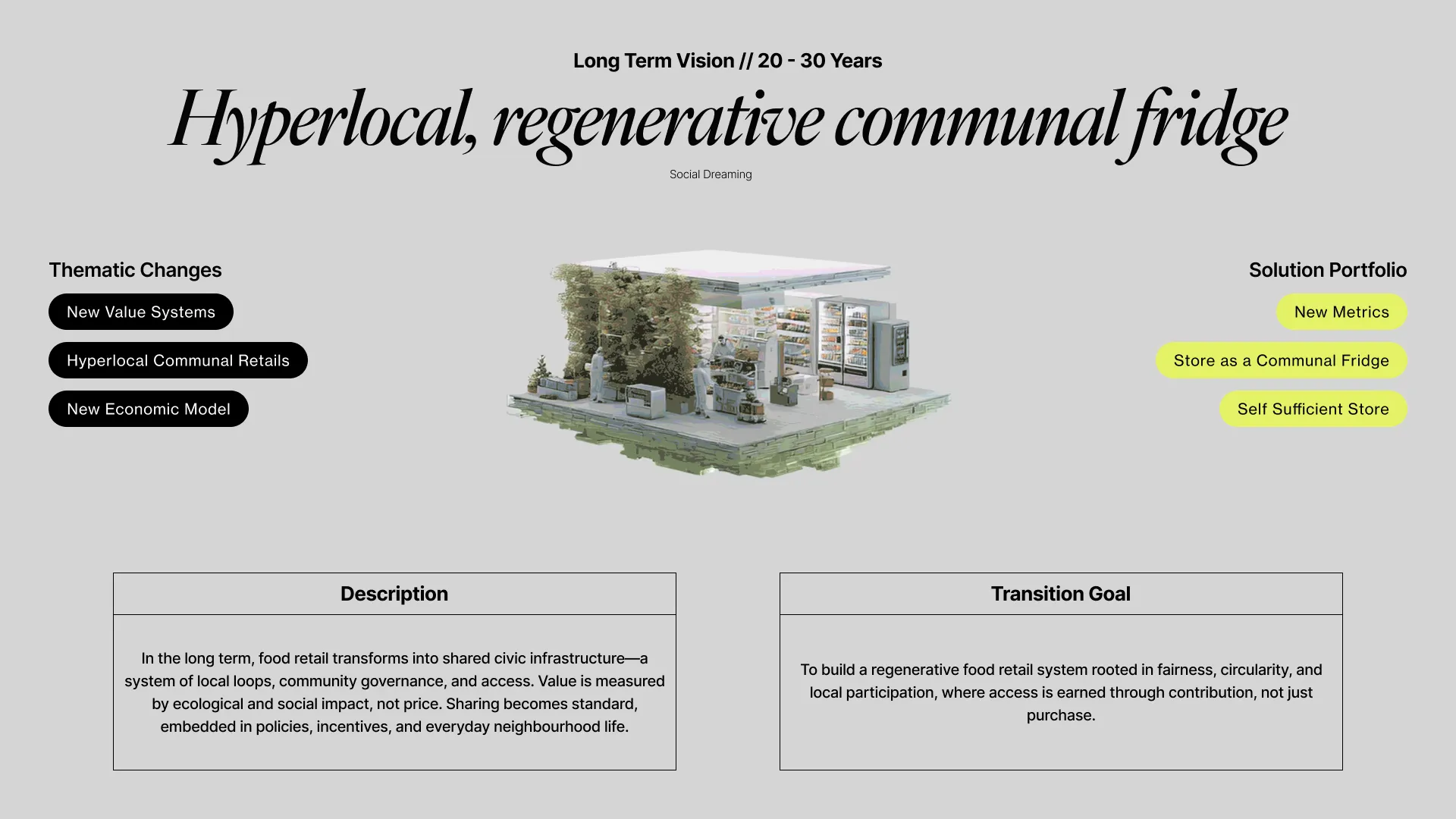

Transition Design Framework

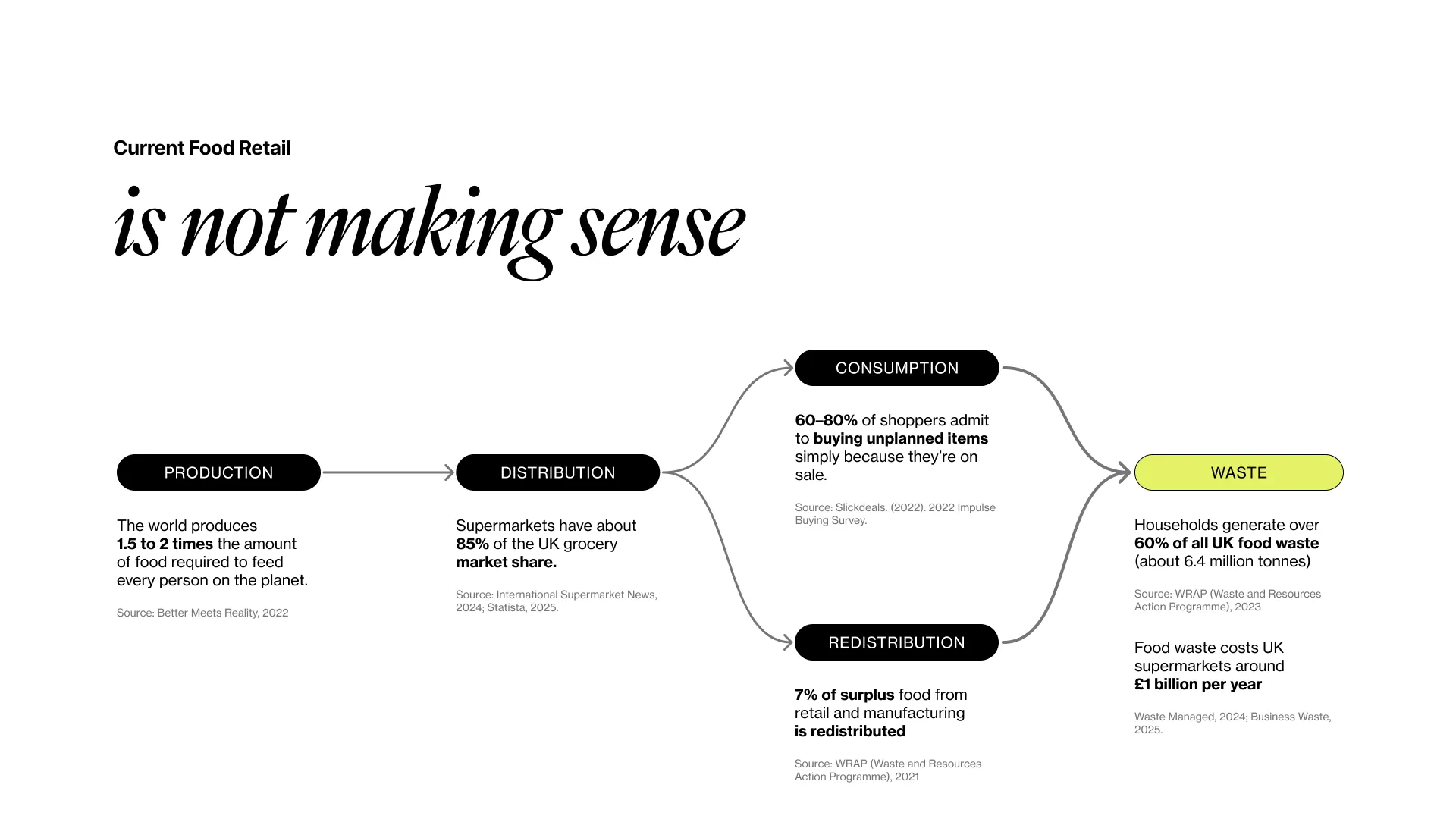

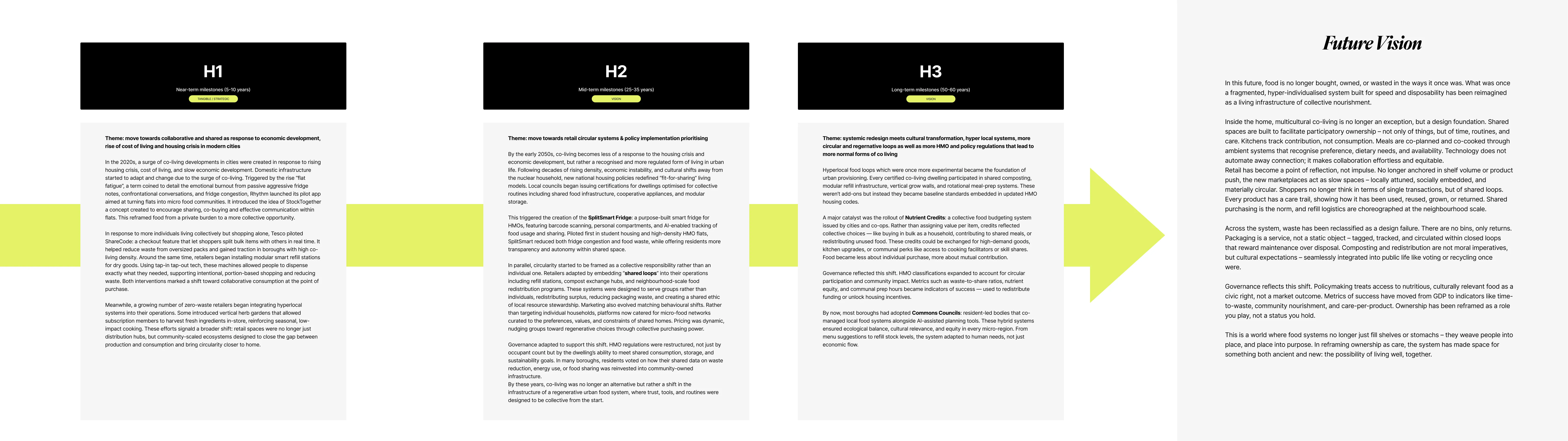

To move from analysis to intervention, we adopted the Transition Design framework (Irwin et al., 2015) to understand the historical, interconnected, and value-laden nature of the current food retail system. Transition Design emphasises that wicked problems, like food waste, overconsumption, and unsustainable retail practices, cannot be solved with isolated fixes. They require long-term, multi-level change grounded in societal values and systemic understanding.

Using Transition Design lenses, we explored how the current food system has become locked-in over time through:

- Economic structures: Volume-based pricing, sales-driven KPIs, and retail real estate norms

- Cultural narratives: Individual responsibility, ownership as control, “value for money” = bulk

- Infrastructure inertia: Supermarket design, packaging formats, domestic fridge layouts

- Policy fragmentation: Siloed regulation across food waste, packaging, and housing

These overlapping forces reinforce the existing system, making alternative models feel difficult, risky, or even unimaginable to mainstream actors.

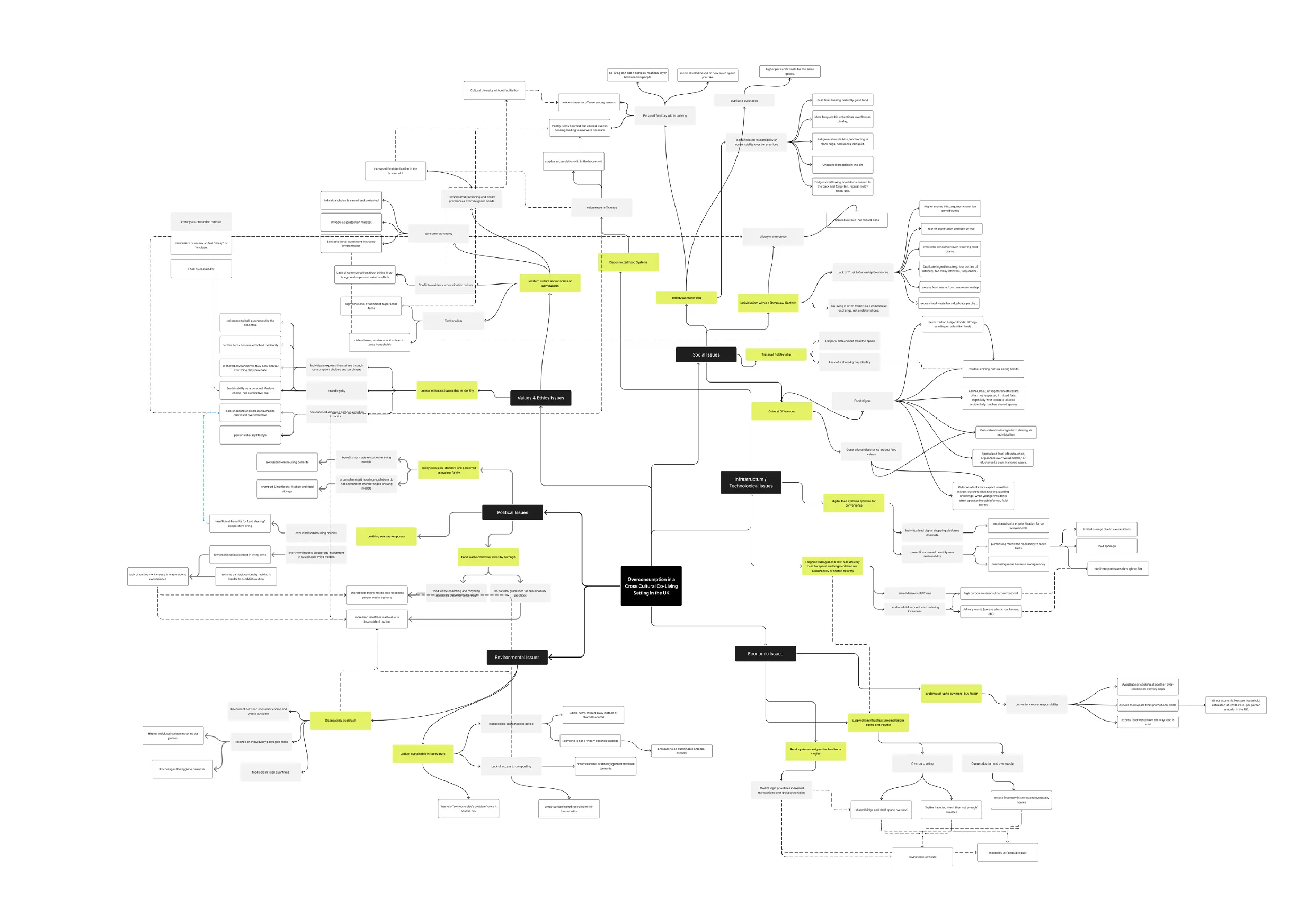

Wicked Problem Mapping

We built a Wicked Problems Map to surface and connect the complex, interdependent drivers of overconsumption and waste in packaged food systems. This mapping exercise identified factors spanning social norms, retail incentives, packaging design, infrastructure constraints, and individual behaviours. By visualising these interrelations, we made visible the complexity and entanglement of the problem space. We wanted to expose the full complexity of the challenge, showing how factors like retail incentives, social norms, and infrastructure reinforce each other. This helped us avoid simplistic solutions and frame the problem as truly systemic.

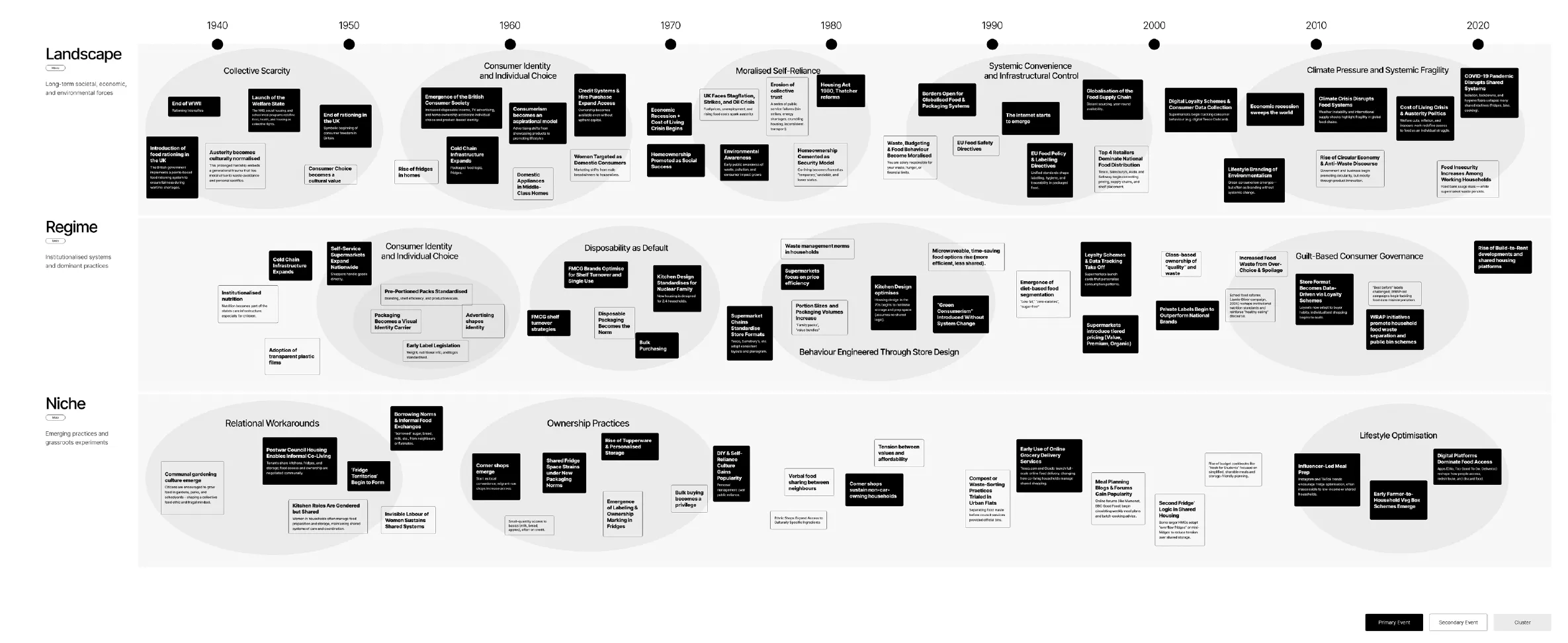

Multilevel Perspective Mapping

We applied the Multi-Level Perspective (MLP) framework to analyse how ownership practices in food consumption have evolved over time across three levels: 1. Landscape (broad cultural and societal trends), 2. Regime (dominant systems and infrastructures), and 3. Niche (emerging innovations and alternatives). We created a timeline to track these shifts from the 1940s to today. We aimed to understand how ownership norms and systems evolved over time. By placing current practices in historical context, we could see why certain behaviours persist and identify moments when meaningful change became possible.

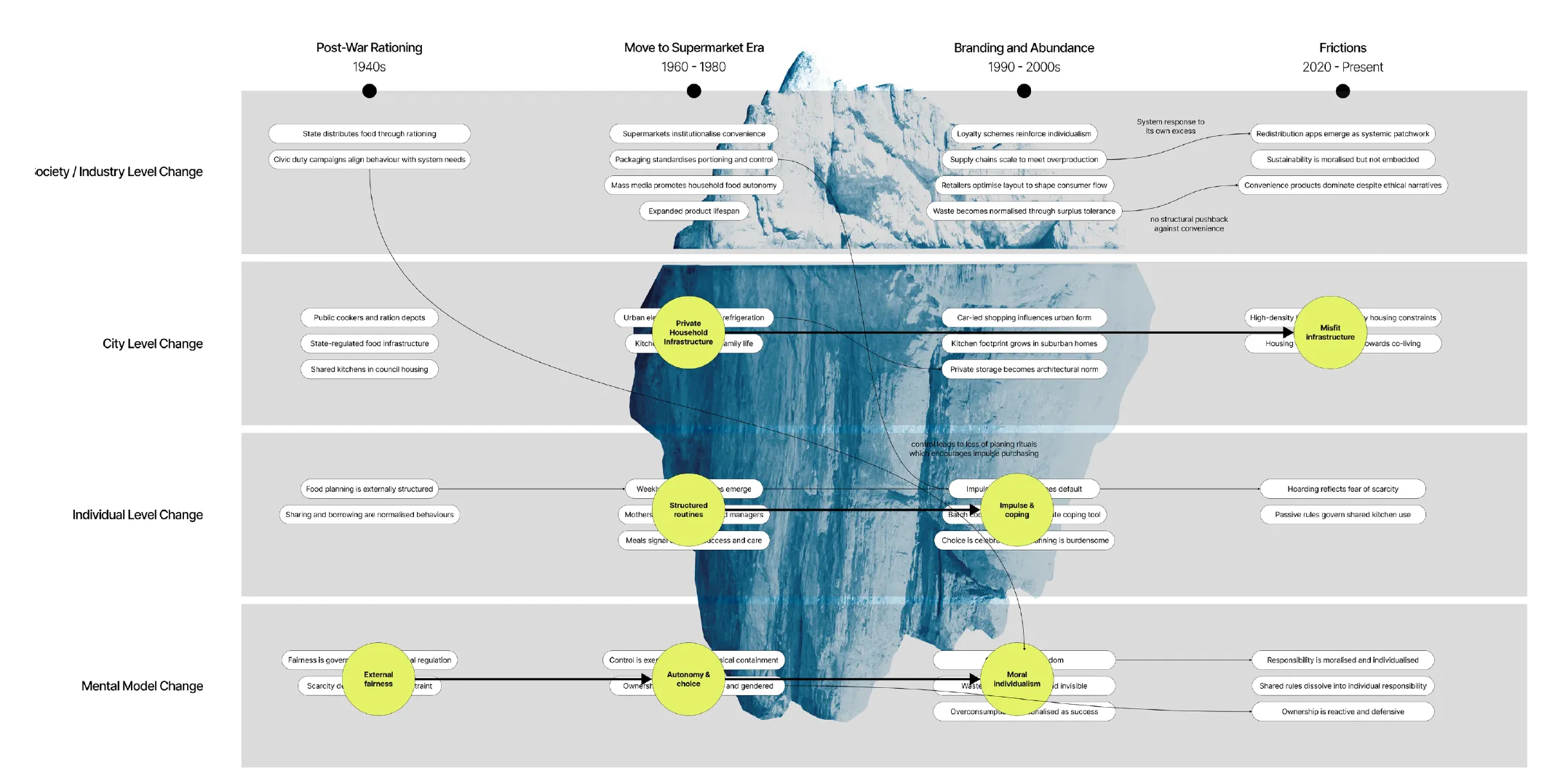

Iceberg Model

We used the Iceberg Model to structure our analysis across four levels: visible events and behaviours, underlying patterns, systemic structures, and mental models. This visual diagram traced how everyday practices like bulk buying, convenience shopping, and food hoarding are shaped by deeper infrastructural, cultural, and psychological drivers.. We wanted to look beneath everyday actions to find the patterns, structures, and mindsets driving them. This helped us identify deeper areas to target for lasting change.

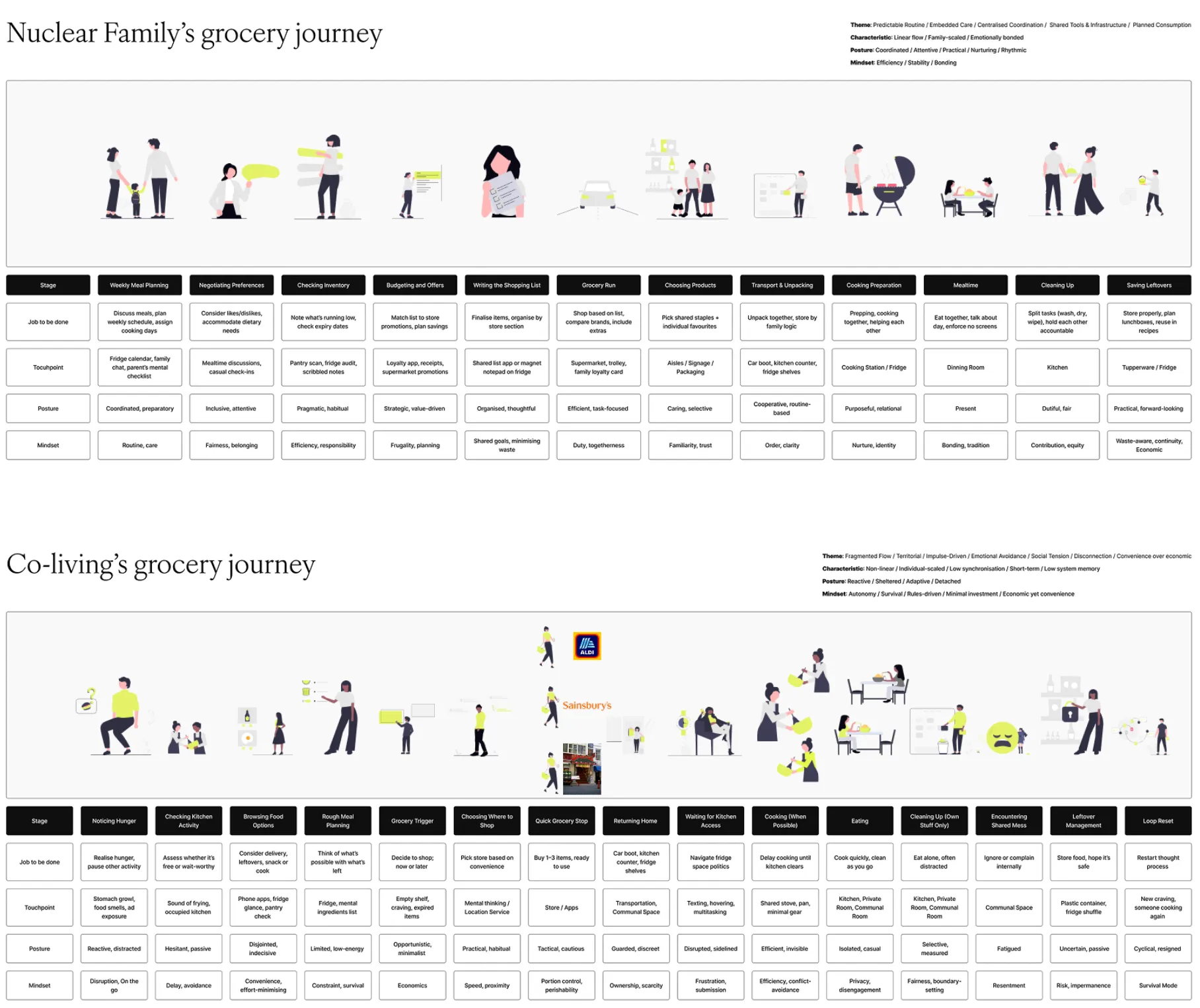

Our MLP (Multi-Level Perspective) analysis revealed the nuclear family as a dominant model that has historically shaped mainstream food systems, driving packaging formats, retail design, and shopping behaviours optimised for predictable, centralised household coordination.

To better understand the real-world implications of this legacy, we mapped and compared grocery journeys in both nuclear family and co-living contexts. This allowed us to see how ownership norms and routines that work well in a family setting can break down in shared living arrangements, leading to frictions like territorial behaviour, spoilage, and waste.

Nuclear Family: Linear, Coordinated, and Habitual

The nuclear family’s grocery journey is structured around planned consumption and collective routines:

- Decisions are made jointly and in advance (e.g. weekly meal planning, budgeting, inventory checks)

- Touchpoints are often centralised (e.g. shared fridge, loyalty app, bulk pantry)

- Tasks are distributed but oriented around shared goals like efficiency, stability, and family bonding

- The journey is predictable and repetitive, allowing retailers to target offers, packaging sizes, and promotions accordingly

Co-living: Fragmented, Impulsive, and Isolated

In contrast, the co-living journey is marked by impulse, individual agency, and minimal coordination:

- Each individual follows their own logic, often driven by emotional hunger, mood, or convenience

- The journey is non-linear, looping between personal need and shared kitchen bottlenecks

- Coordination happens only in shared spaces (e.g. fridge, bin, table), and often leads to tension, duplication, or territorial behaviour

- Decision-making is reactive, and ownership is ambiguous e.g. leftover food becomes a source of anxiety or waste

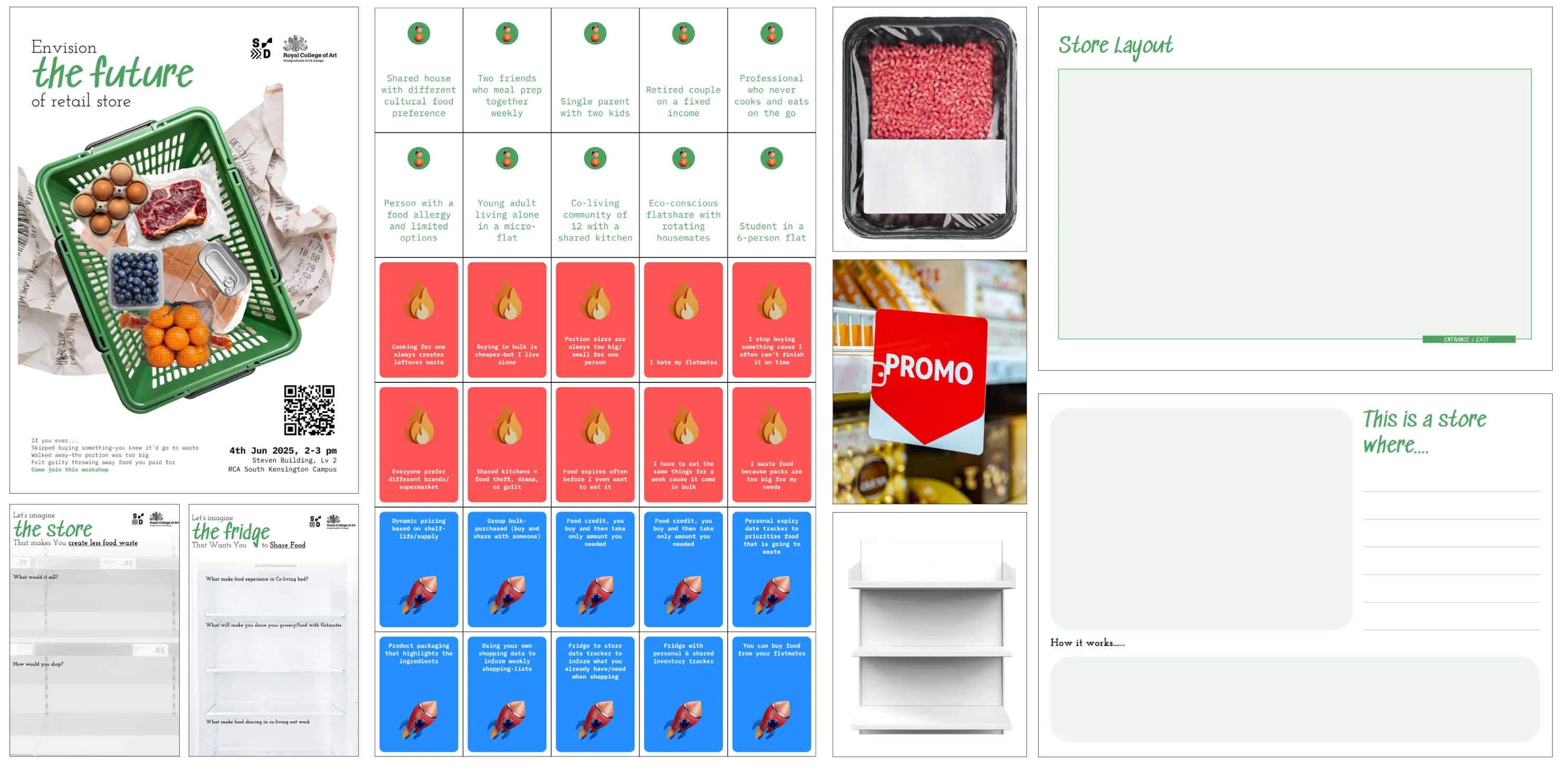

Ethnographic Research

To ensure our systemic analysis was grounded in real behaviours, emotions, and frictions, we conducted ethnographic research with individuals living in shared flats and co-living environments across London.

While our system maps and behaviour settings offered a bird’s-eye view of structural barriers, this phase allowed us to zoom into the messiness of everyday life, where routines are improvised, fridges are shared, and ownership is constantly negotiated.

Contextual Interview

We conducted in-depth ethnographic interviews with residents of co-living flats to understand their real-world practices, frustrations, and adaptations around shared food ownership. Participants also provided photos of their shared fridges to document space constraints, storage habits, and maintenance norms. We wanted to ground our systemic analysis in lived experience. By speaking directly with people navigating shared kitchens and storage, we could capture rich, situated details that reveal how ownership practices are negotiated, avoided, or break down in daily life.

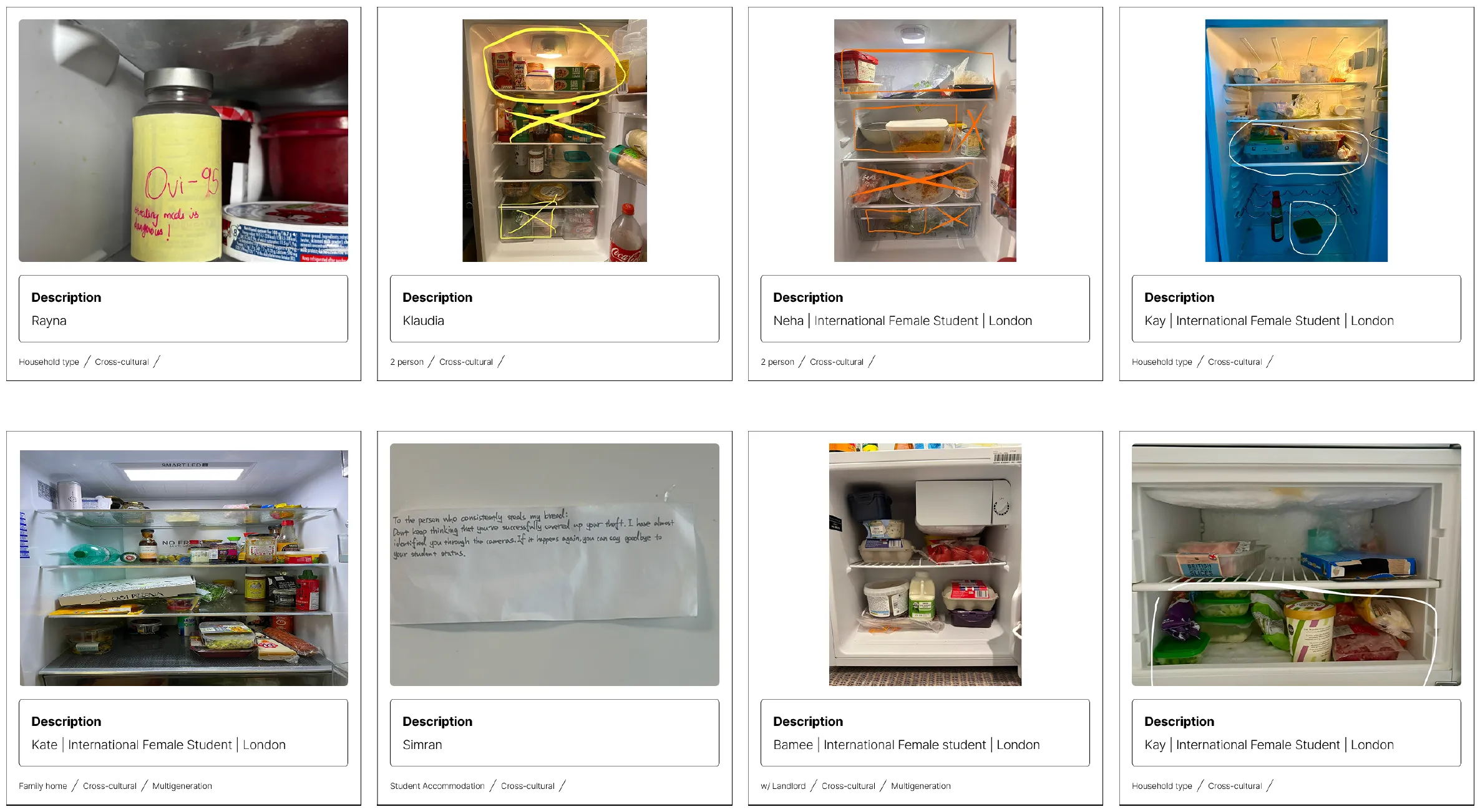

Across multiple interviews and kitchen walkthroughs, one object consistently emerged as a symbol of conflict, control, and compromise:

the fridge.

In co-living environments, the fridge becomes more than just a storage space, it becomes a territorial boundary, a power marker, and an emotional flashpoint.

Cultural Probe

To further explore how ownership is enacted and negotiated in everyday life, we conducted cultural probes focused specifically on the fridge in shared households.

This simple yet revealing method helped us visualise ownership in physical space, uncovering the silent rules and relational dynamics that shaped food interaction.

What We Found:

- Designated Shelves: Most fridges were split by individual, not meal type. Each shelf became a mini-territory, even when inefficiently used.

- Unclaimed Zones: Areas left untouched because the “designated person” wasn’t using them, or had moved out but no one dared to reassign their space.

- Label Strategies: Use of tape, post-its, or colour-coded containers to signal ownership and discourage accidental use

- Emotional Boundaries: Items like shared milk or sauces often caused subtle tension, people either over-contributed (to avoid guilt) or avoided use entirely (to avoid conflict)

- Invisible Waste: Expired items remained untouched because no one felt responsible enough, or empowered enough, to throw them away

This probe reinforced our earlier conclusion: ownership in shared living is rarely discussed, but constantly acted out. And because domestic infrastructure (like fridges) doesn’t support fluid or collective ownership, tension and waste build up silently.

These insights helped us reframe the fridge as a critical site of intervention, not just in homes, but in the design of food retail systems themselves.

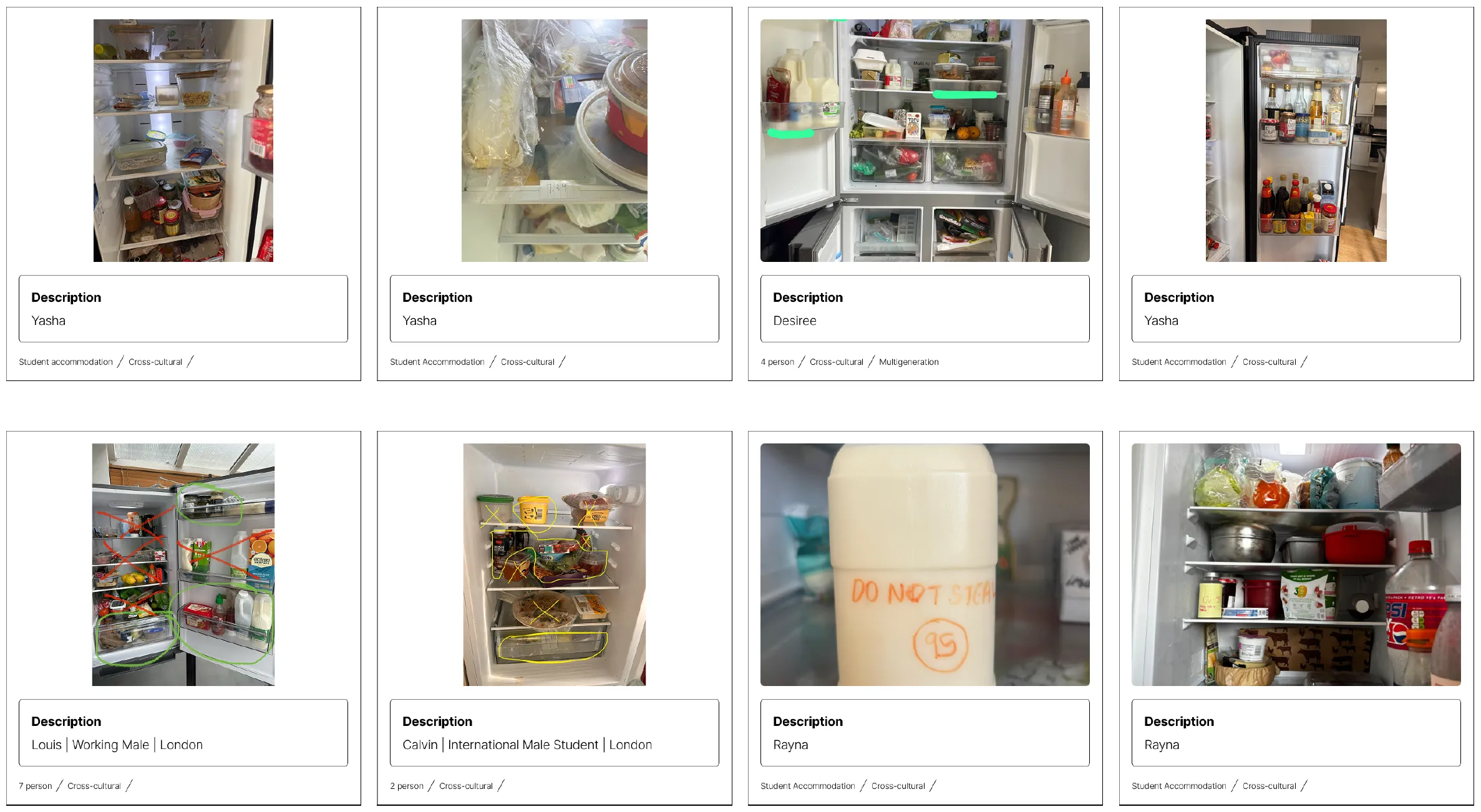

Thematic Analysis

We aimed to move from raw interview data to structured insights that could inform design. By codifying themes across participants, we identified patterns of shared pain points and systemic barriers that interventions would need to address to make collaborative ownership viable.

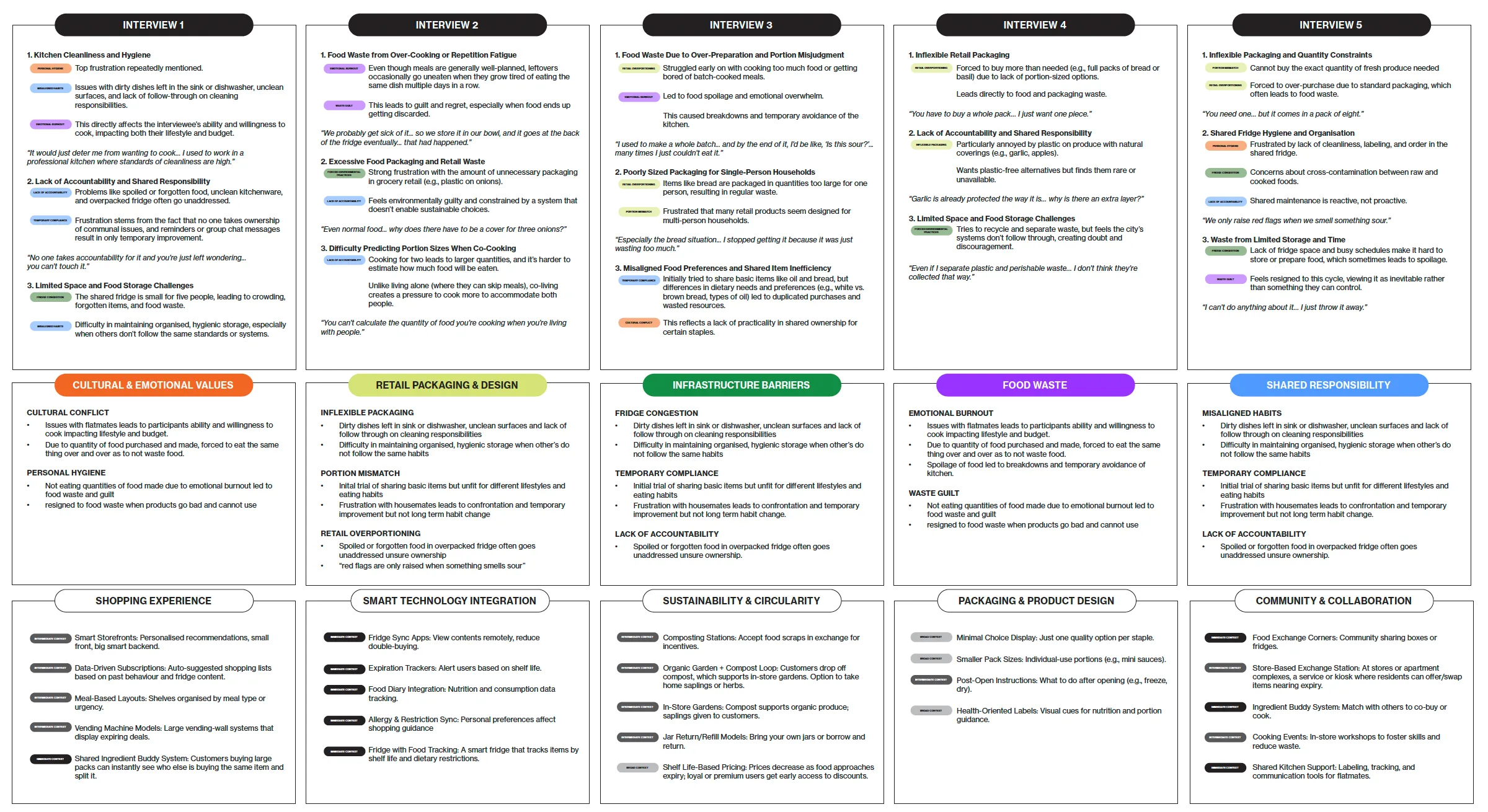

Casual loop diagram

We translated these coded themes into a detailed system map. This map visualises the interconnections between factors like storage limits, emotional burnout, retail overportioning, hygiene expectations, and accountability breakdowns. We highlighted feedback loops and leverage points within the co-living context. We wanted to understand not just what the problems are, but how they interrelate and reinforce one another. Mapping the system helped us see where small design interventions could disrupt negative cycles or enable positive change toward shared responsibility.