Research

ClosePreliminary Research

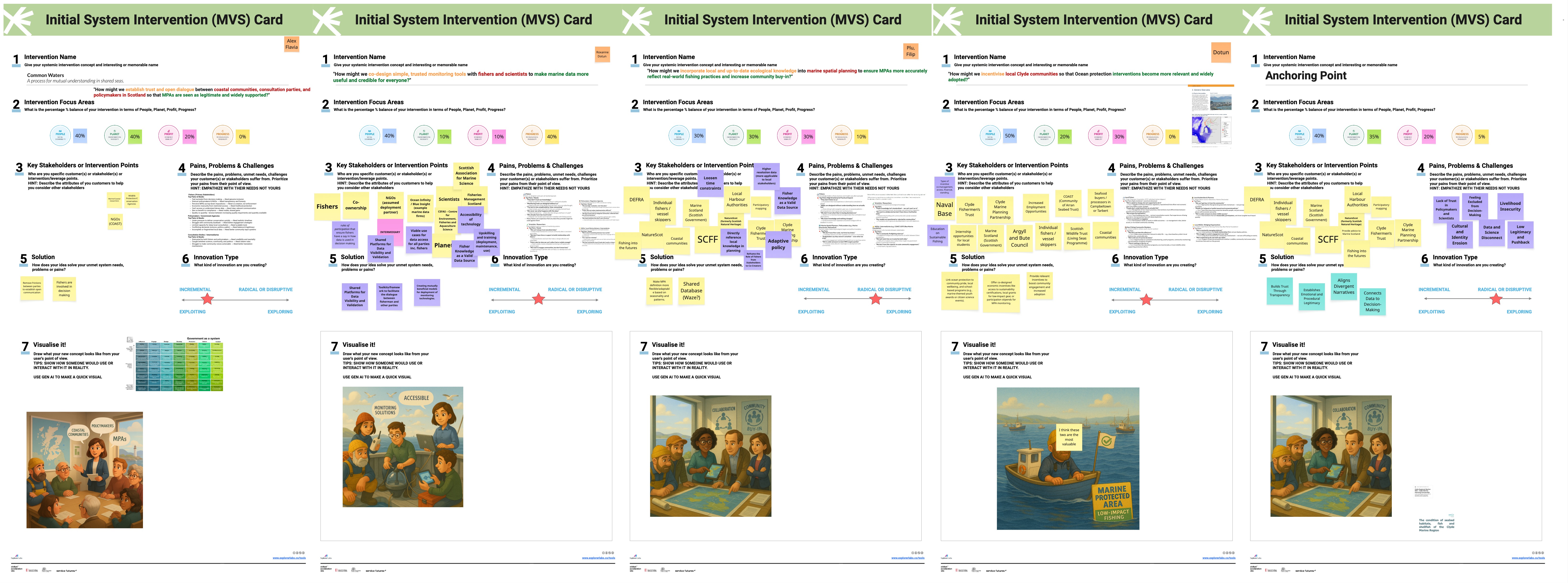

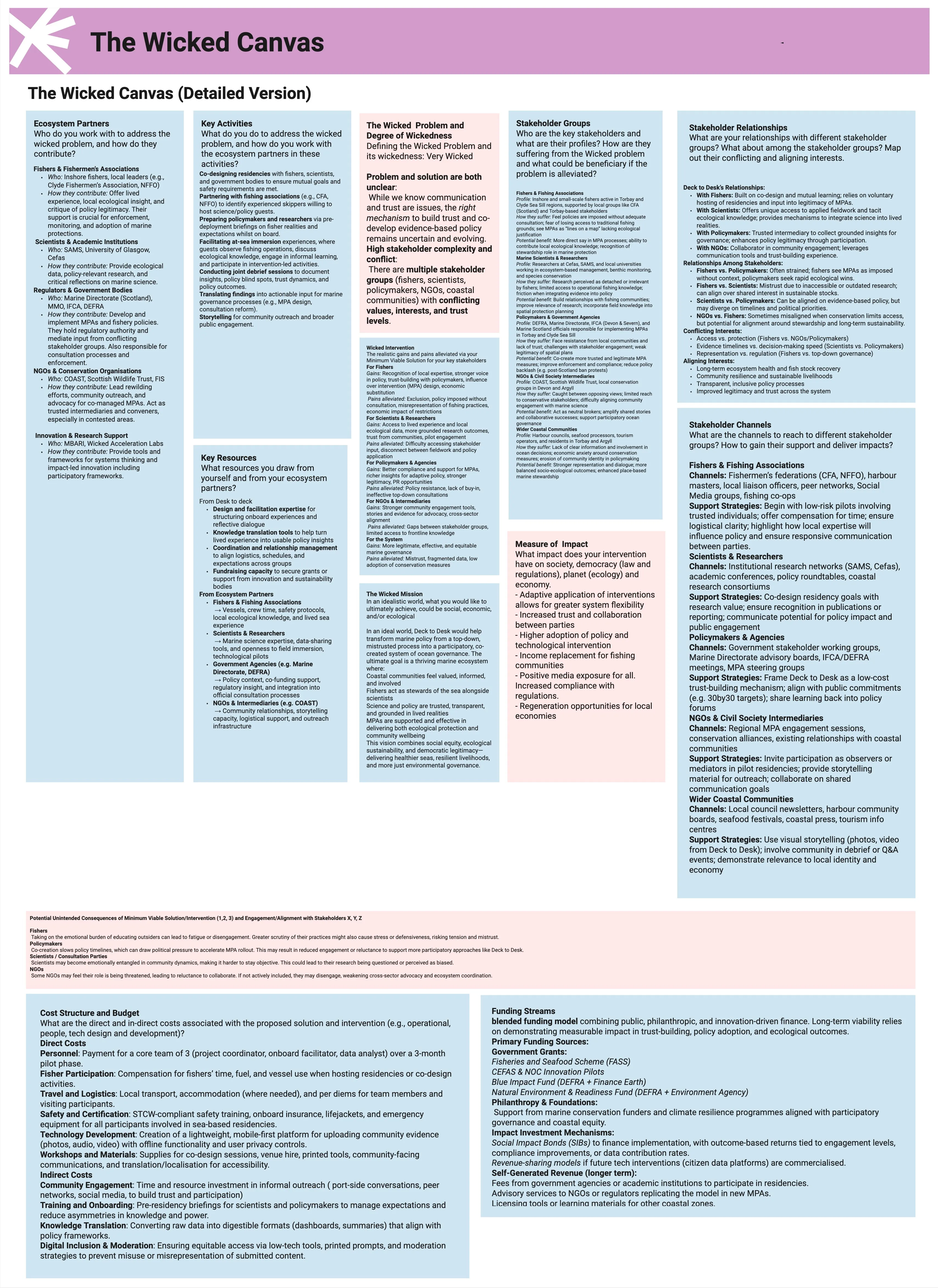

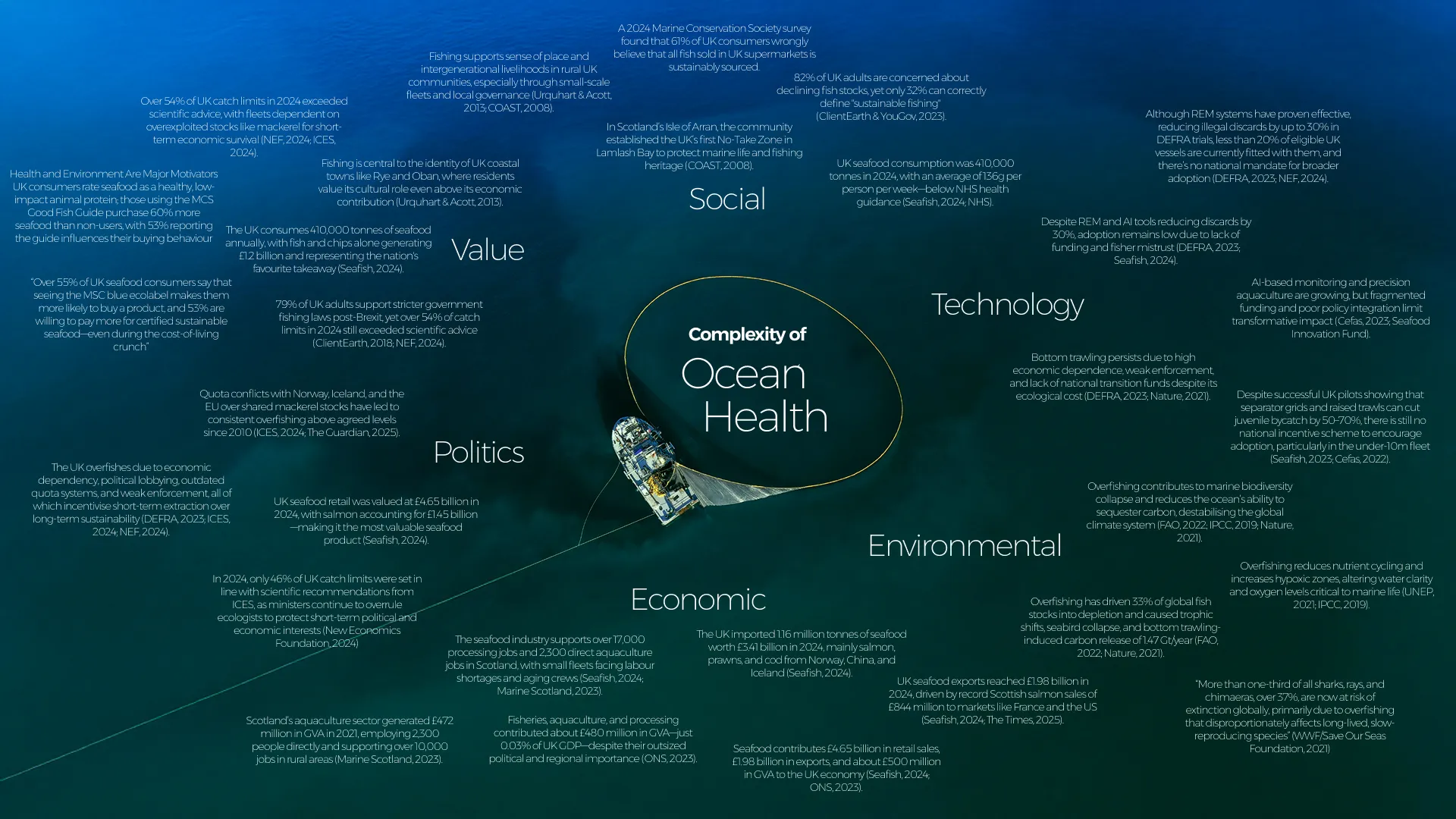

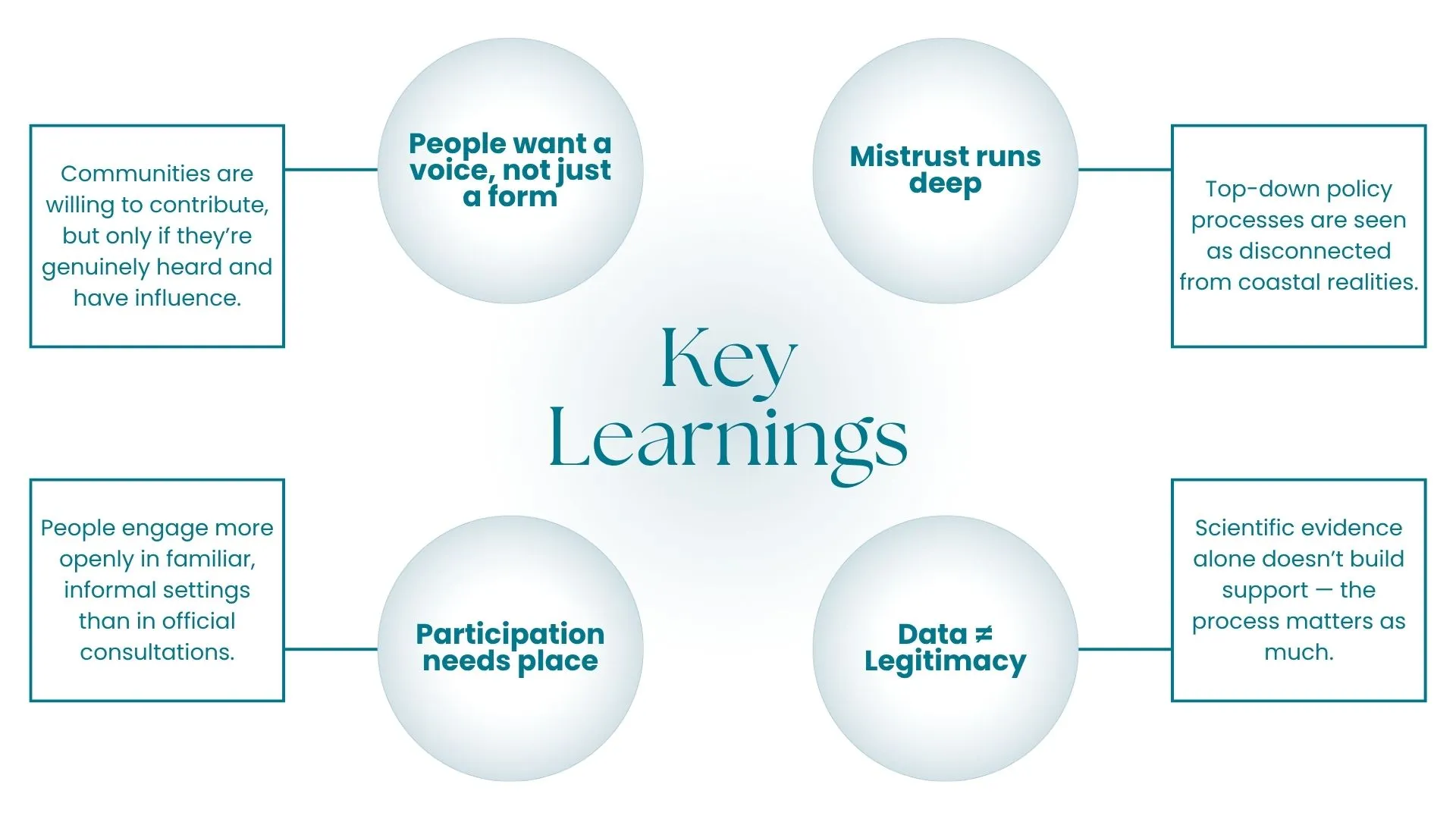

Following our STEEPV scan, we conducted desktop research to identify recurring tensions and opportunities within the UK fishing system. From ecological reports and policy reviews to community-led marine initiatives, a number of cross-cutting themes emerged, including mistrust between fishers and regulators, the disconnect between science and lived experience, and the uneven distribution of technological access.

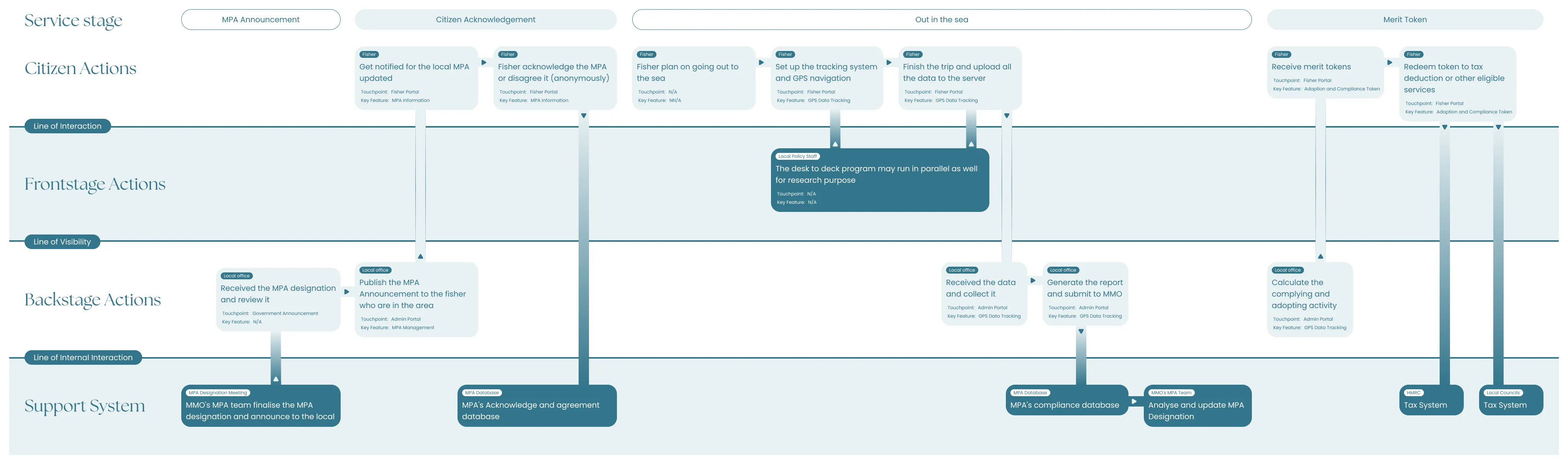

To move beyond isolated observations, we employed systems thinking tools to understand the deeper structures shaping behaviour:

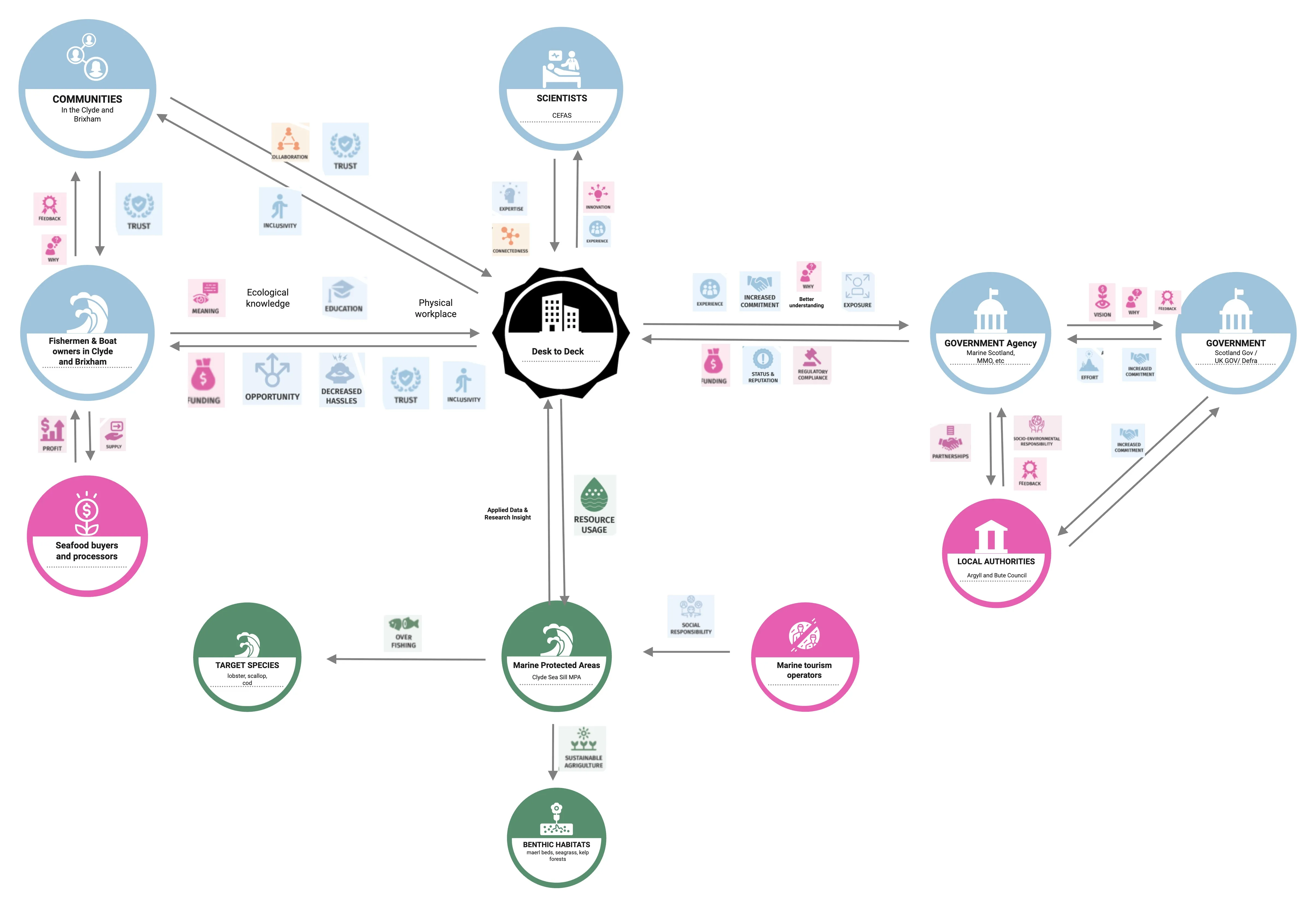

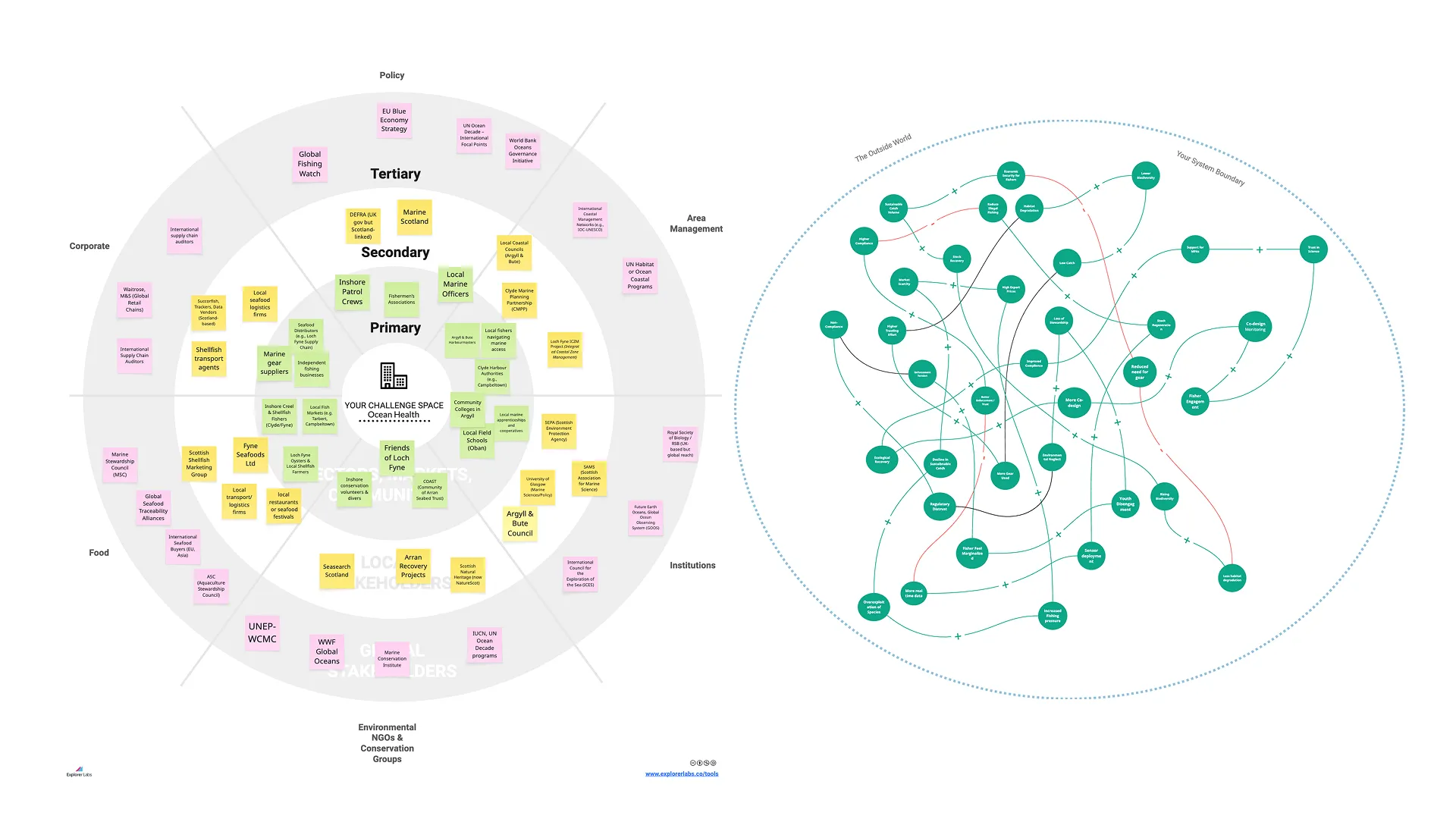

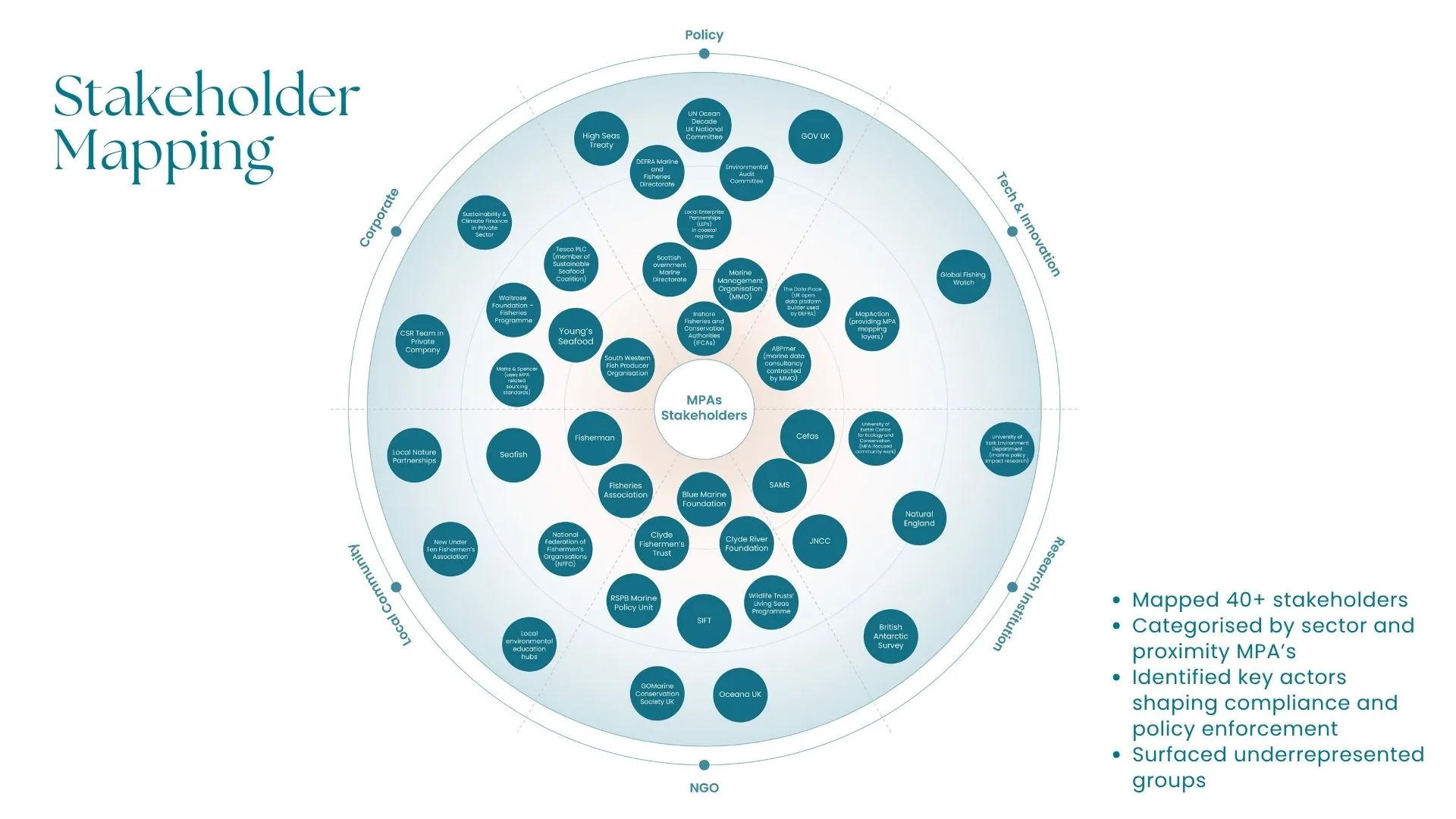

Stakeholder Map

We created a multi-level stakeholder map to visualise the complex web of actors influencing, and affected by, ocean health and fishing practices in the UK. These included:

- Primary stakeholders: Local fishers, government agencies, marine ecologists

- Secondary stakeholders: NGOs, tech developers, seafood buyers, researchers

- Tertiary stakeholders: Media, education institutions, and the wider public

This mapping helped us identify who needed to be part of the conversation, not just for insight, but for legitimacy and long-term systems change.

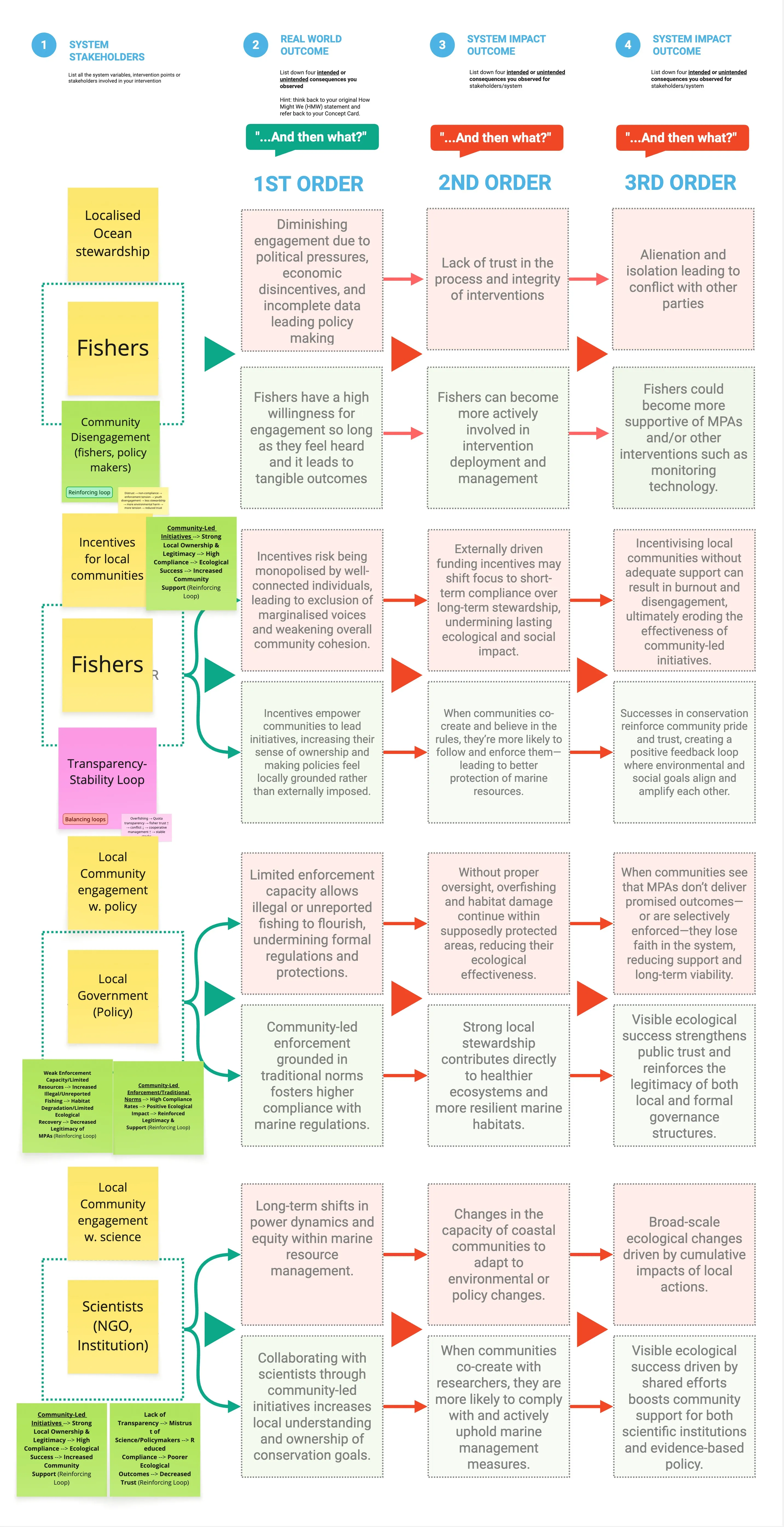

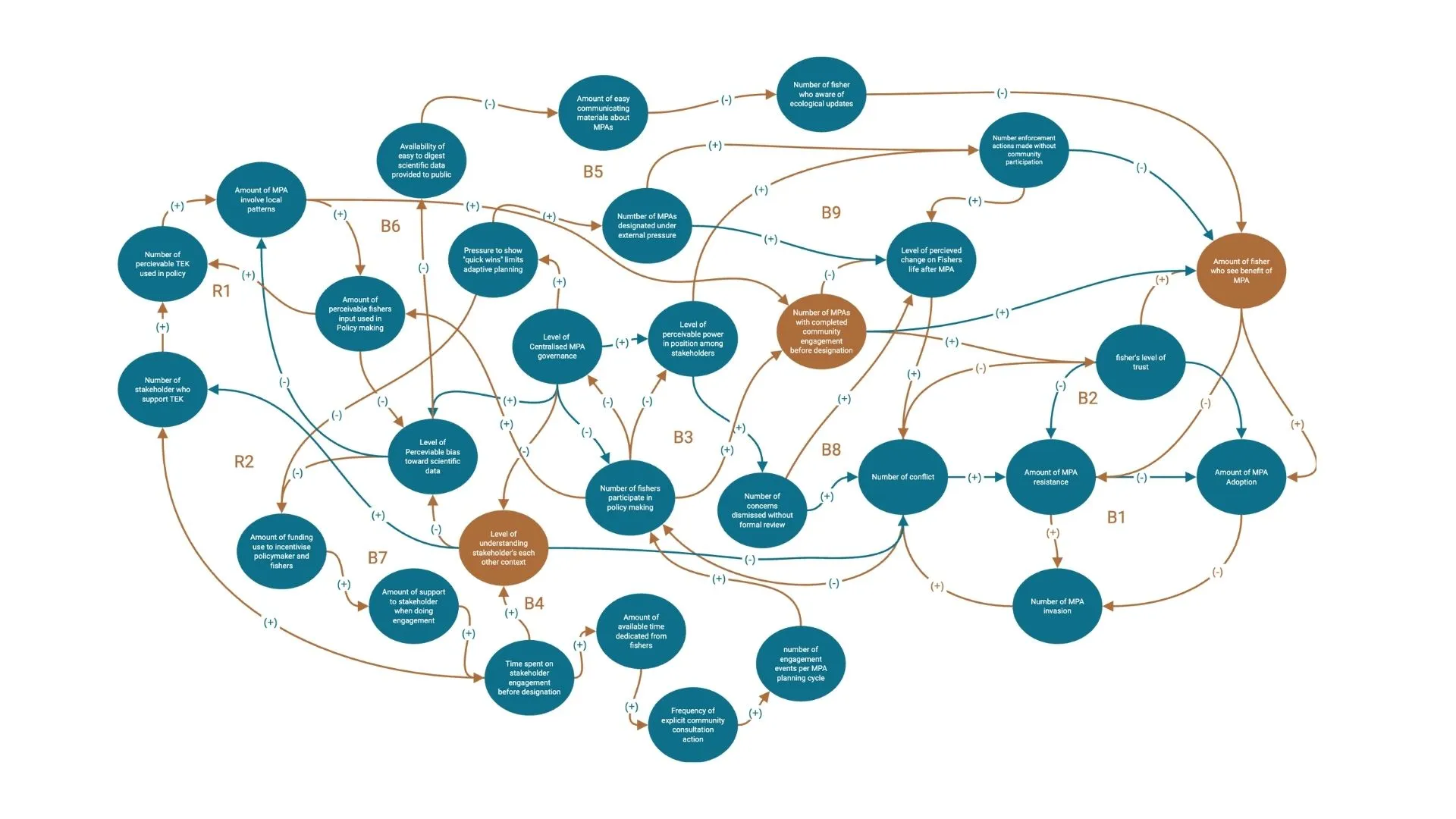

Causal Loop Diagram

To explore system dynamics, we built a causal loop diagram that revealed reinforcing and balancing feedback loops

These tools helped us clarify not just who to engage, but which topics could serve as leverage points for more effective and inclusive interventions.

Field Research & Insights

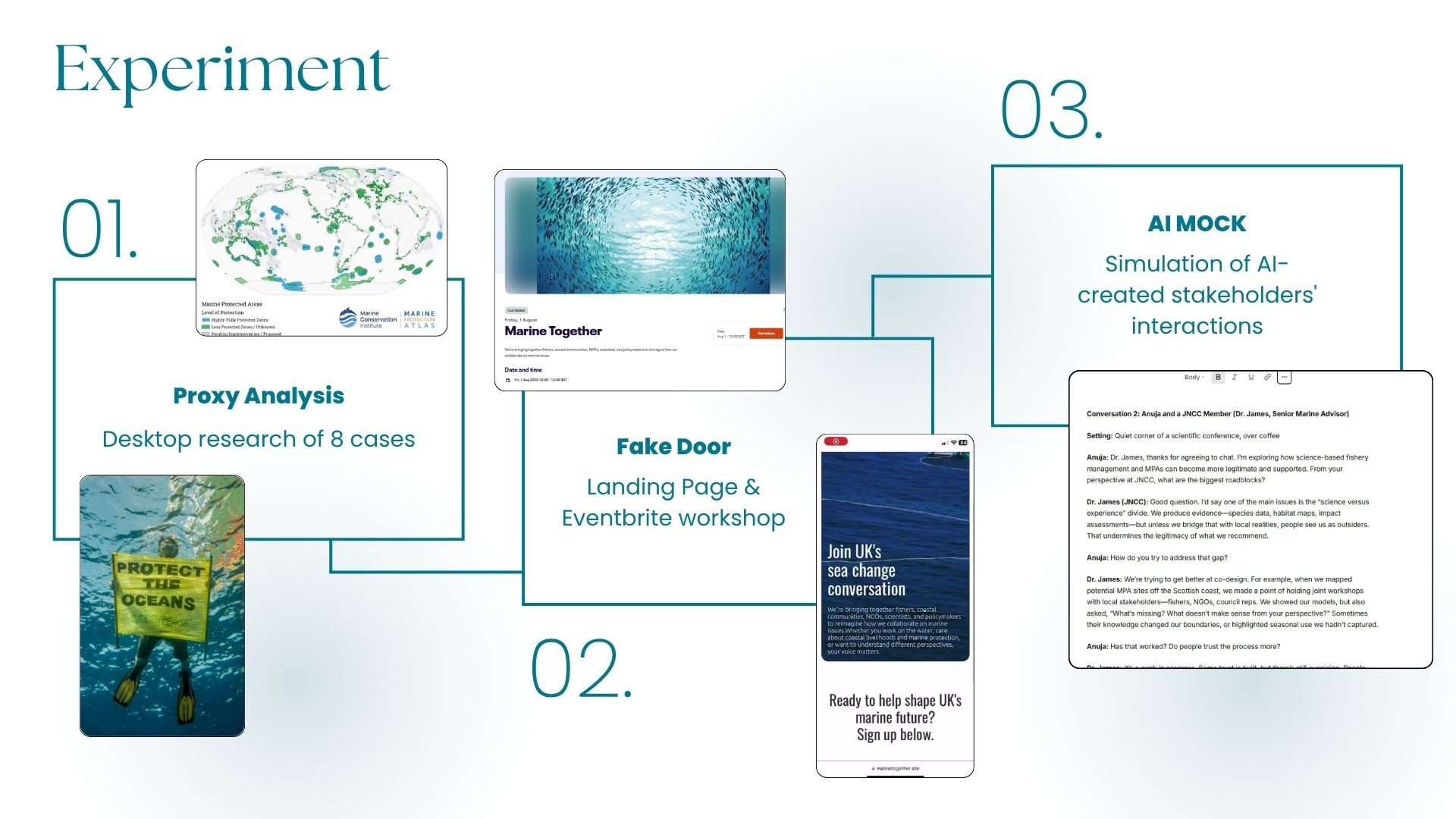

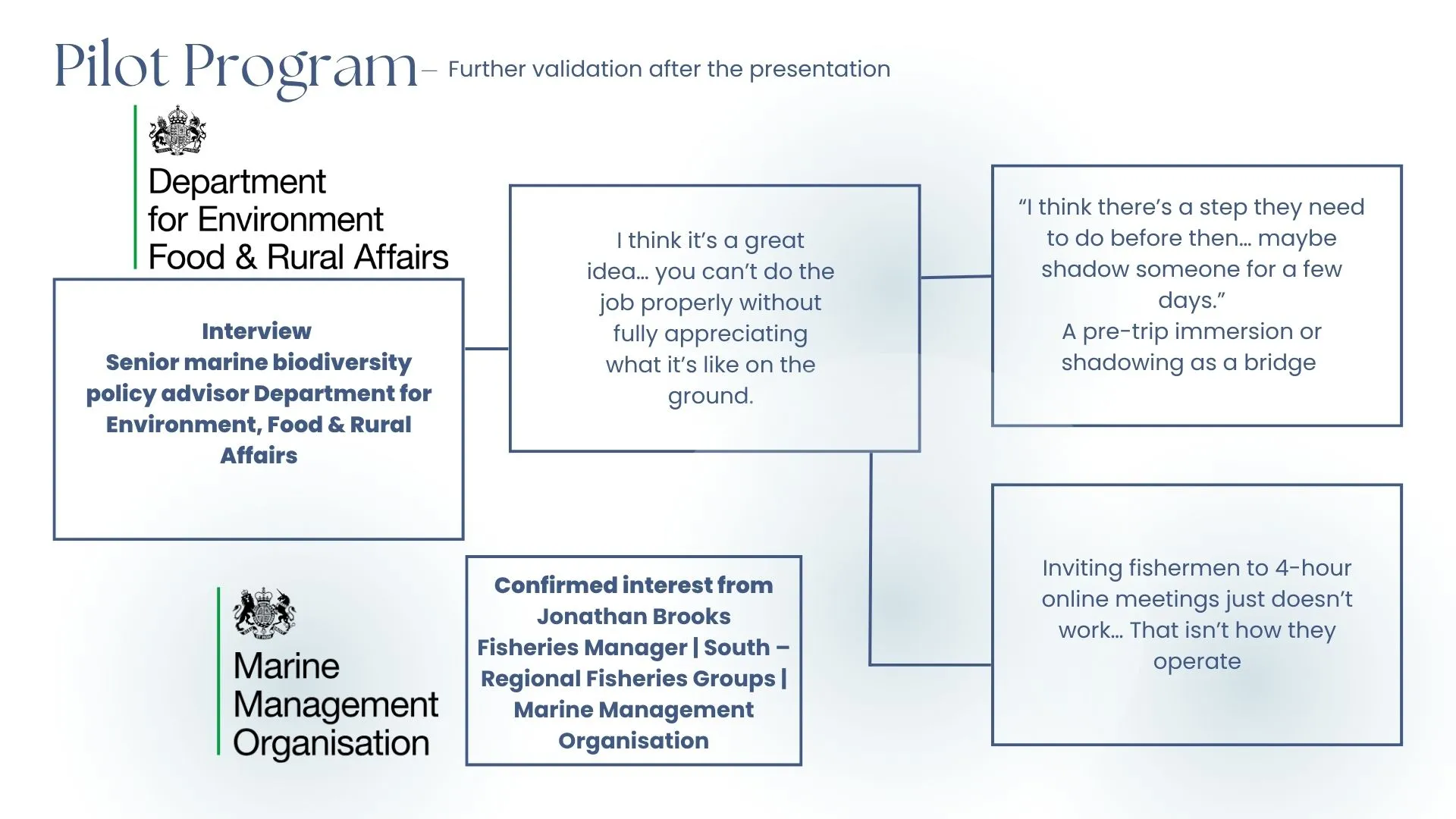

To deepen our systems understanding and validate emerging hypotheses, we conducted a mix of online stakeholder interviews and on-site fieldwork, engaging directly with actors across the fishing system.

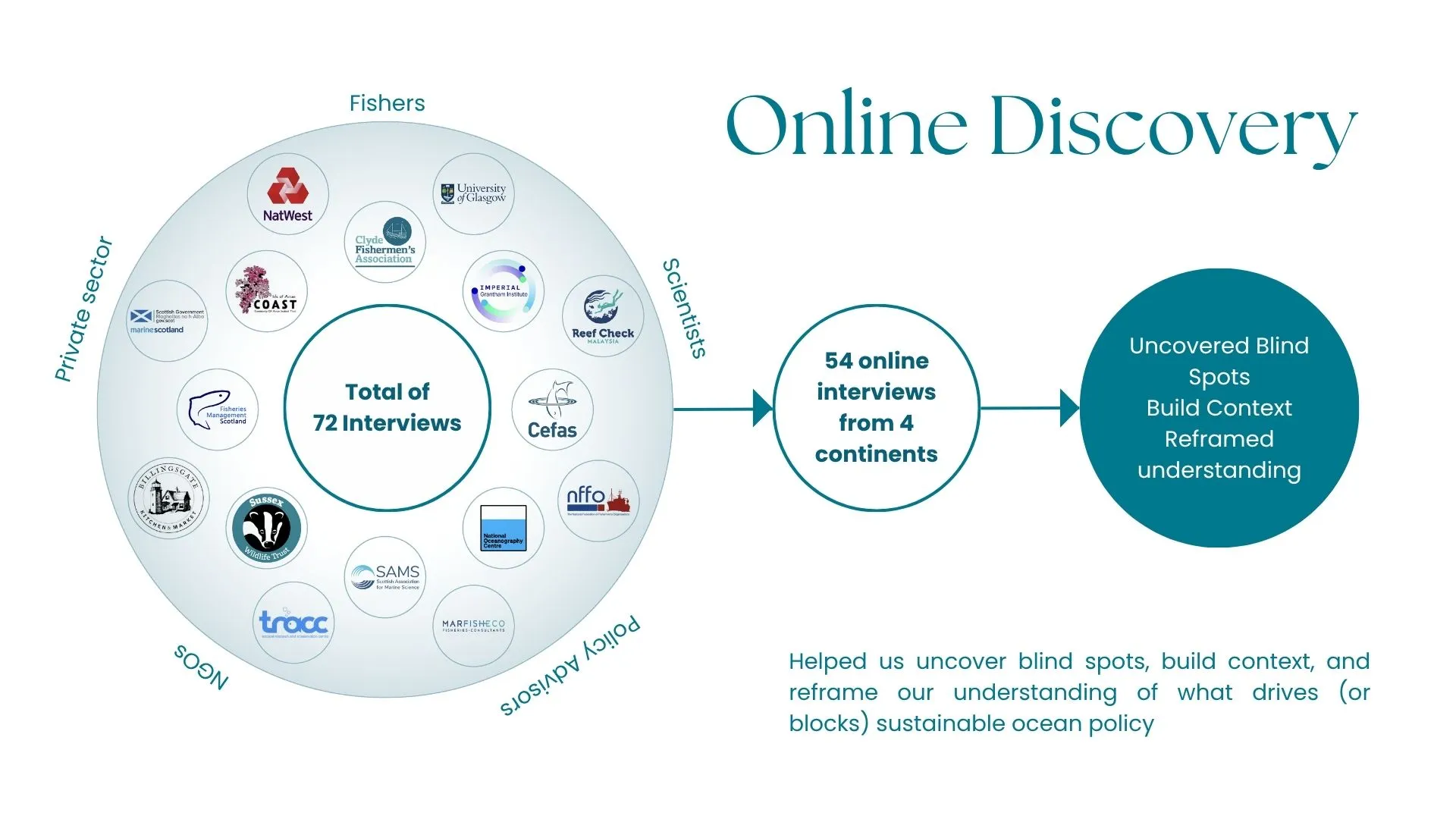

Online Discovery

We held 72 interviews with stakeholders from across the world, including scientists, fishers, NGOs, policymakers, and private sector actors. Of these, 54 were conducted online, spanning 4 continents, which helped broaden our perspective beyond the UK context.

Through these conversations, we were able to:

- Uncover blind spots in our assumptions

- Build contextual understanding of local systems

- Reframe our understanding of what drives or blocks sustainable ocean policy

These insights informed where interventions might gain legitimacy and where friction tends to emerge, especially around participation, data ownership, and governance trust.

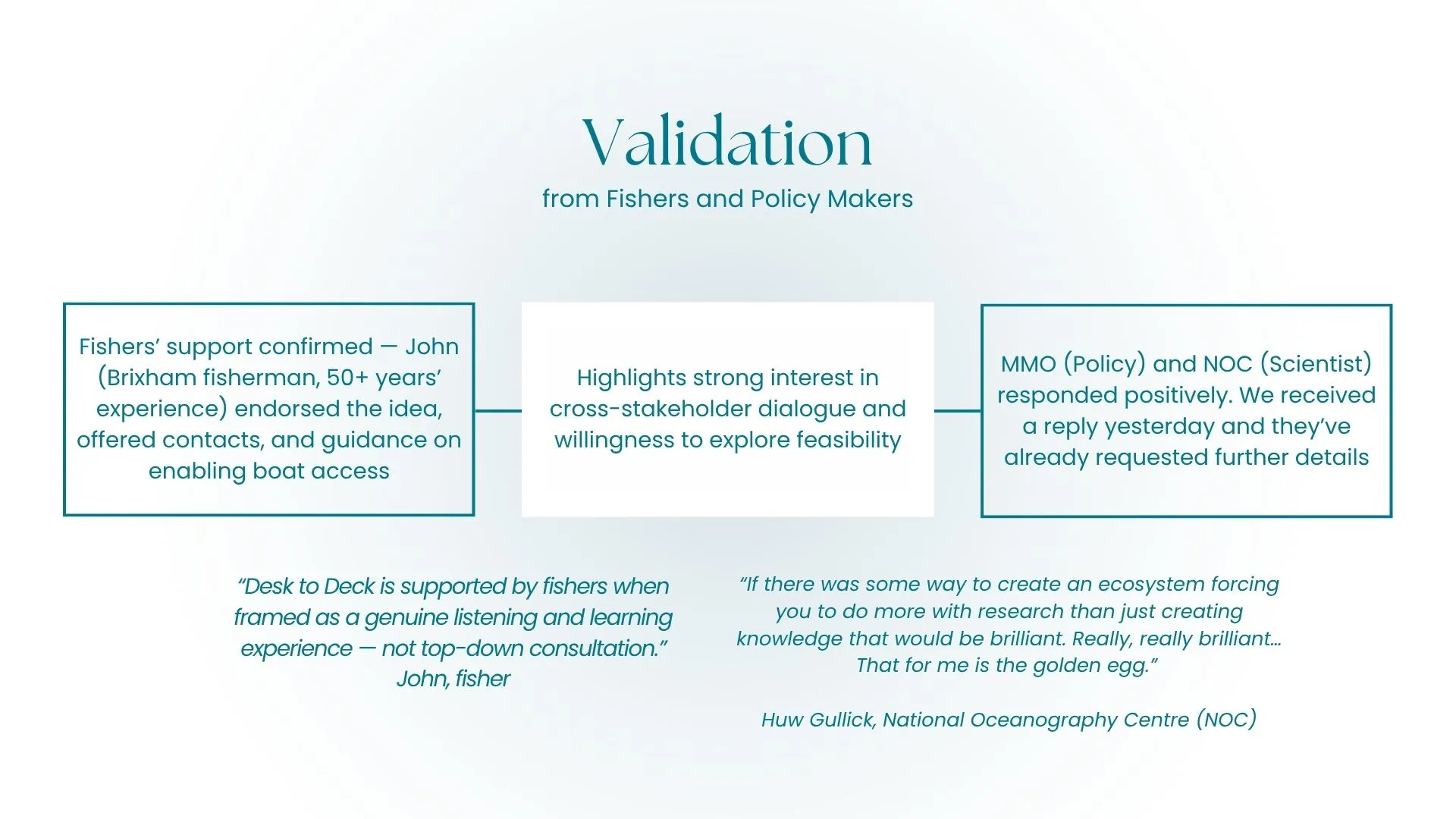

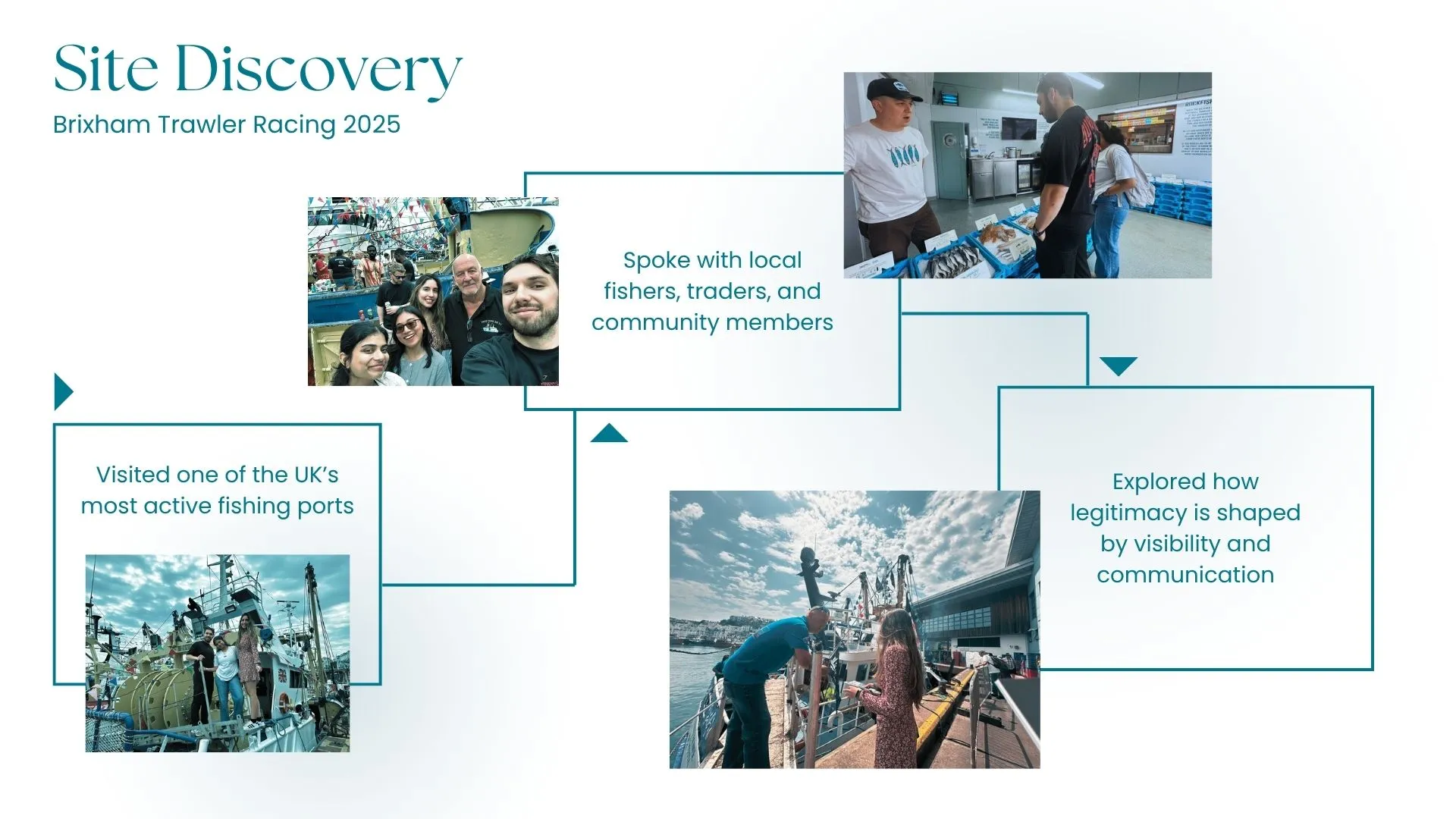

Site Discovery: Brixham, UK

To complement online research with grounded observation, we attended the Brixham Trawler Race 2025, one of the UK’s most active fishing ports and community events. This immersive site visit allowed us to:

- Engage fishers, traders, and community members in informal, trust-building settings

- Observe communication dynamics between fishers and regulatory actors

- Understand how legitimacy is shaped not just by rules, but by visibility, relationships, and local narratives

Summarisation

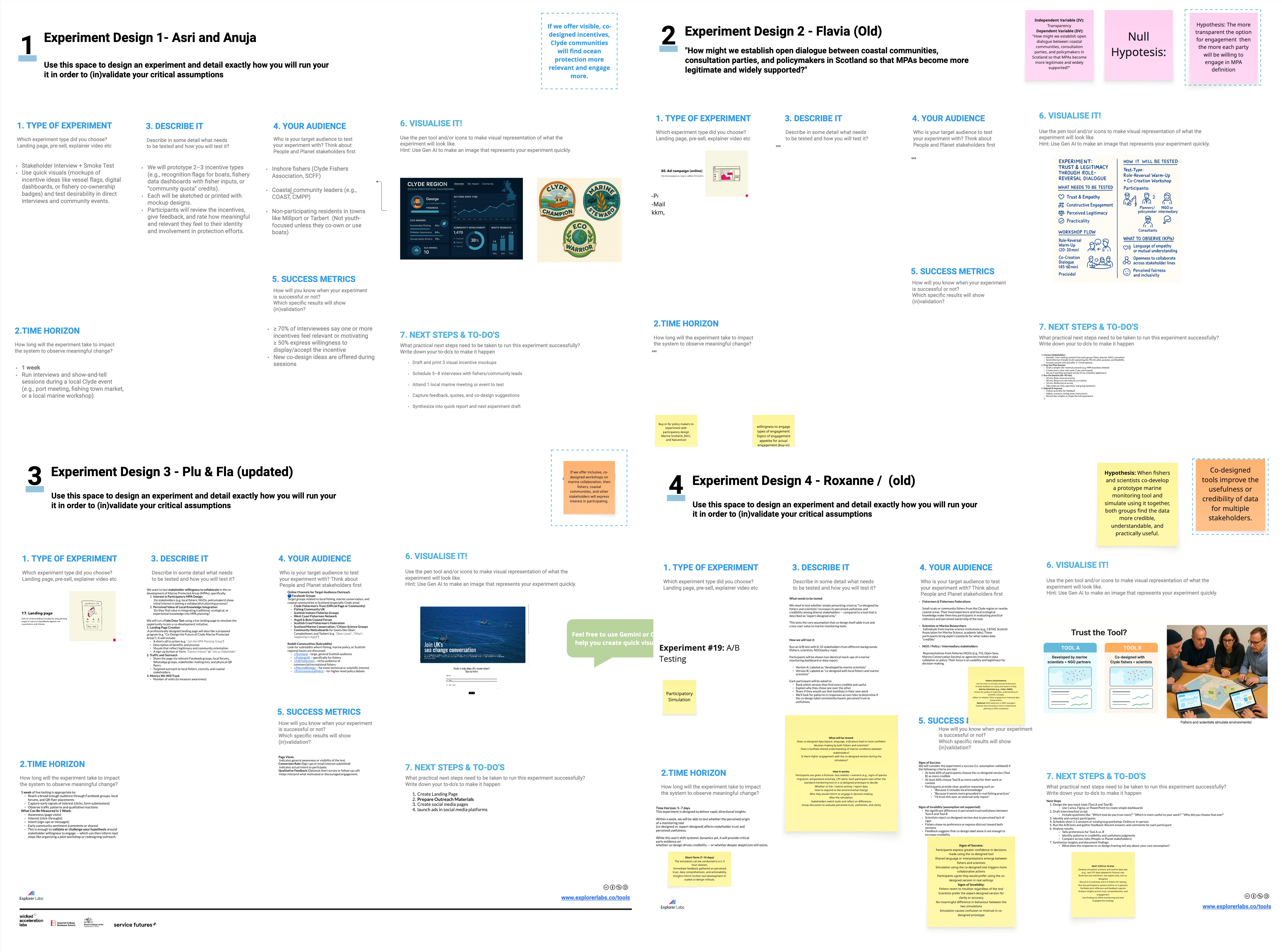

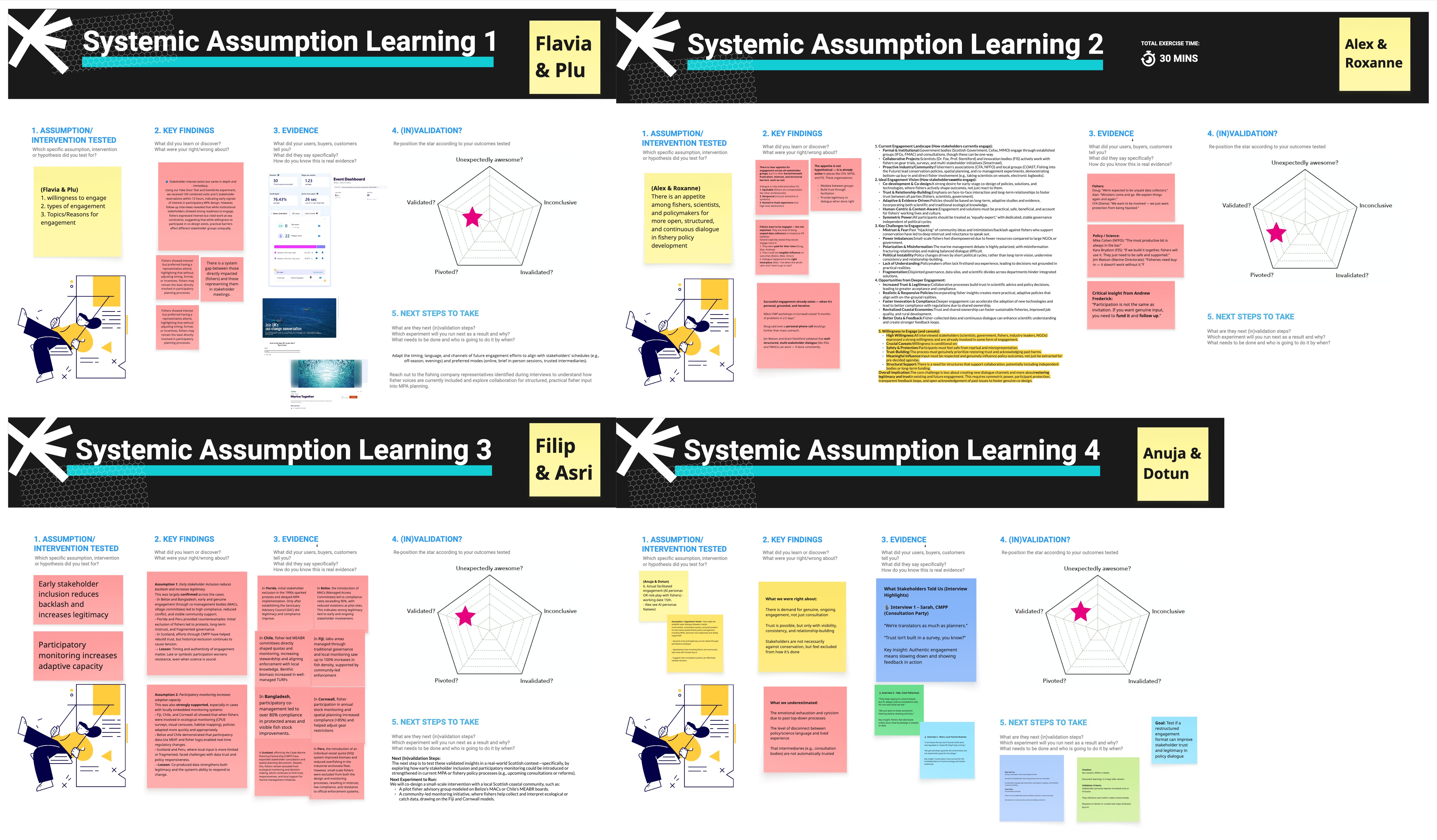

After running the initial set of experiments, we revisited our strategic tools to refine insights and align them with emerging variables:

Stakeholder Map (Updated):

After running our experiments, we revisited the stakeholder map to reflect evolving roles, interests, and power dynamics. New stakeholders emerged, while others shifted in relevance, prompting us to re-cluster and redefine key relationships within the system.

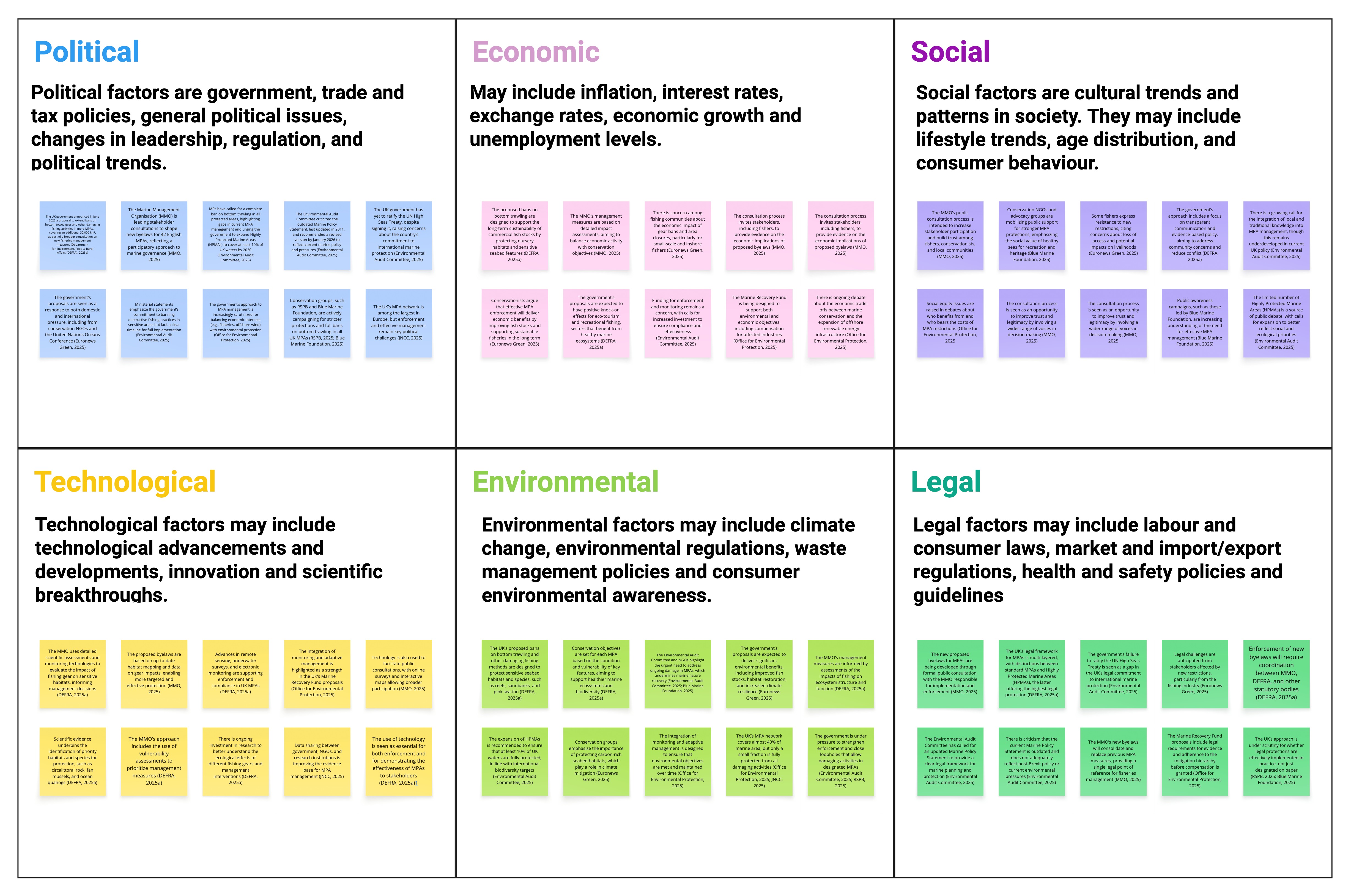

PESTEL Analysis:

We conducted a detailed PESTEL analysis to identify and structure external variables influencing our system. This helped us capture macro-level trends across political, economic, social, technological, environmental, and legal dimensions, informing both short- and long-term considerations.

Causal Loop Diagram (System Map):

Using updated stakeholder insights and PESTEL variables, we reconstructed our causal loop diagram. This allowed us to visualise how feedback loops evolved post-intervention, highlight reinforcing or balancing relationships, and identify new leverage points for systemic change.

Balancing Loop

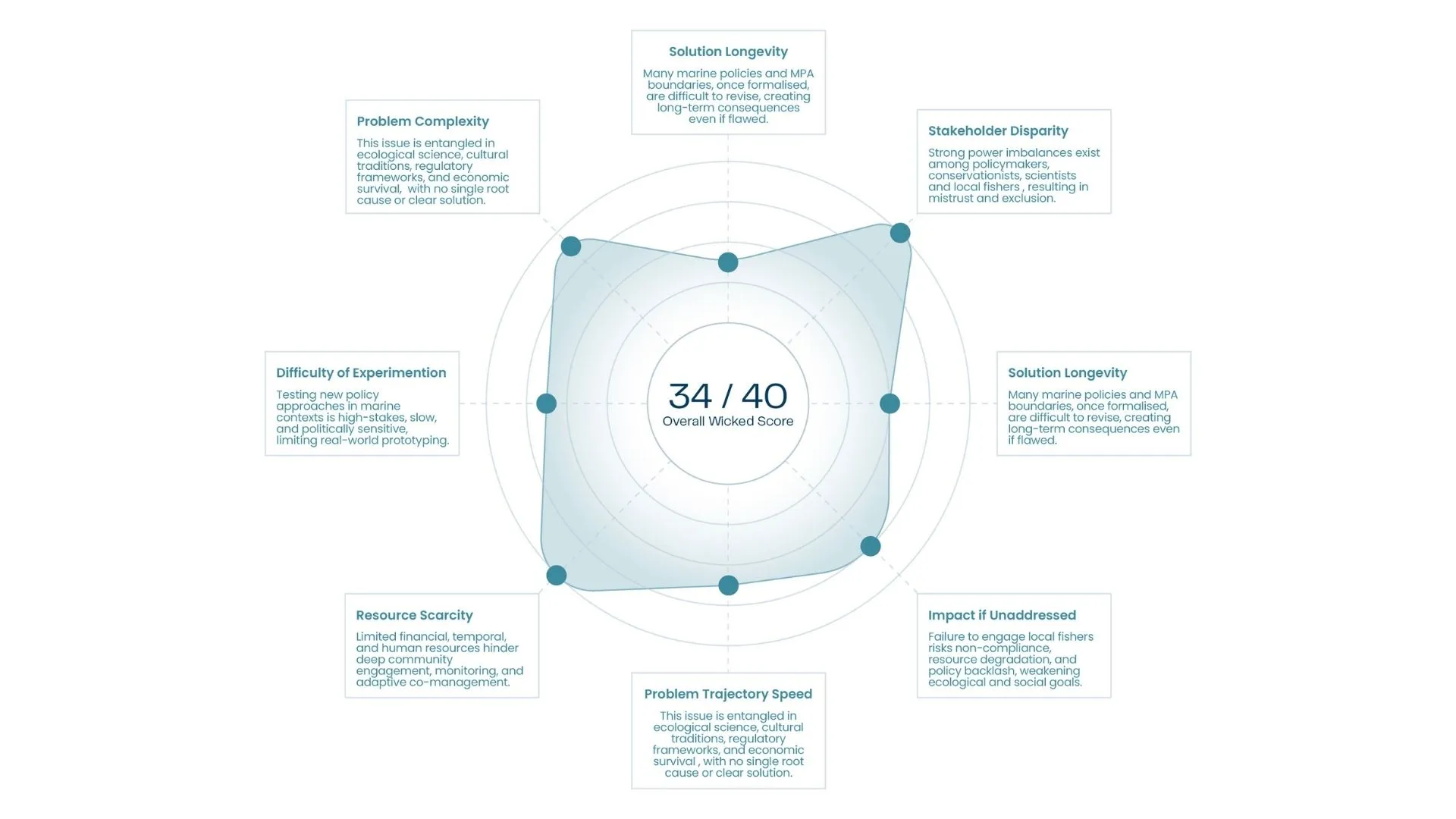

B1: When trust is low, MPA adoption drops. This leads to increased resistance and MPA invasions. The more invasions and resistance, the more mistrust grows, further reducing adoption.

B2: Fisher trust influences how much benefit they perceive from MPAs. Perceived benefit reduces perceived harm, which reinforces trust. But if trust drops (e.g., from top-down enforcement), perceived harm rises, breaking the loop.

B3: Centralised governance increases power disparities, limiting fisher participation. With fewer fishers influencing decisions, conflict rises. The resulting distrust feeds back into conflict and disempowerment.

B4: When fishers have more available time and support, they participate more. But if engagement takes too long or lacks resources, fisher capacity drops, reducing participation and slowing the entire process.

B5: External pressure for quick MPA implementation reduces communication efforts and available digestible materials. Fishers remain unaware or confused about ecological updates, which diminishes their trust and adoption likelihood.

B6: Rushed implementation reduces the use of clear, digestible scientific material. This limits fisher understanding and perceived value of MPAs, weakening knowledge exchange and system learning.

B7: When support (financial and logistic) for engagement is low, participation drops. That means fewer voices in the room and less local knowledge shaping decisions. This reduces the perceived value of engagement, making support harder to justify next time.

B8: Less consultation means more concerns get ignored. When fisher concerns are dismissed, conflict rises. The more conflict, the more defensive the system becomes, reinforcing dismissal practices and excluding fishers further.

B9: The greater the perceived negative impact of MPAs on fisher livelihoods, the less benefit is seen. This undermines support and leads to disengagement or active opposition.

Reinforcing Loop

R1: The more fisher knowledge is integrated into policymaking (through TEK and local patterns), the more trust is built. Trust leads to greater participation and adoption of MPAs, which further increases the likelihood that fisher knowledge continues to be used.

R2: As more stakeholders support TEK, the more TEK is used in policy. This leads to greater inclusion of local patterns, strengthening fisher voice and credibility.