Research

CloseUK's Youth Justice System in 2024

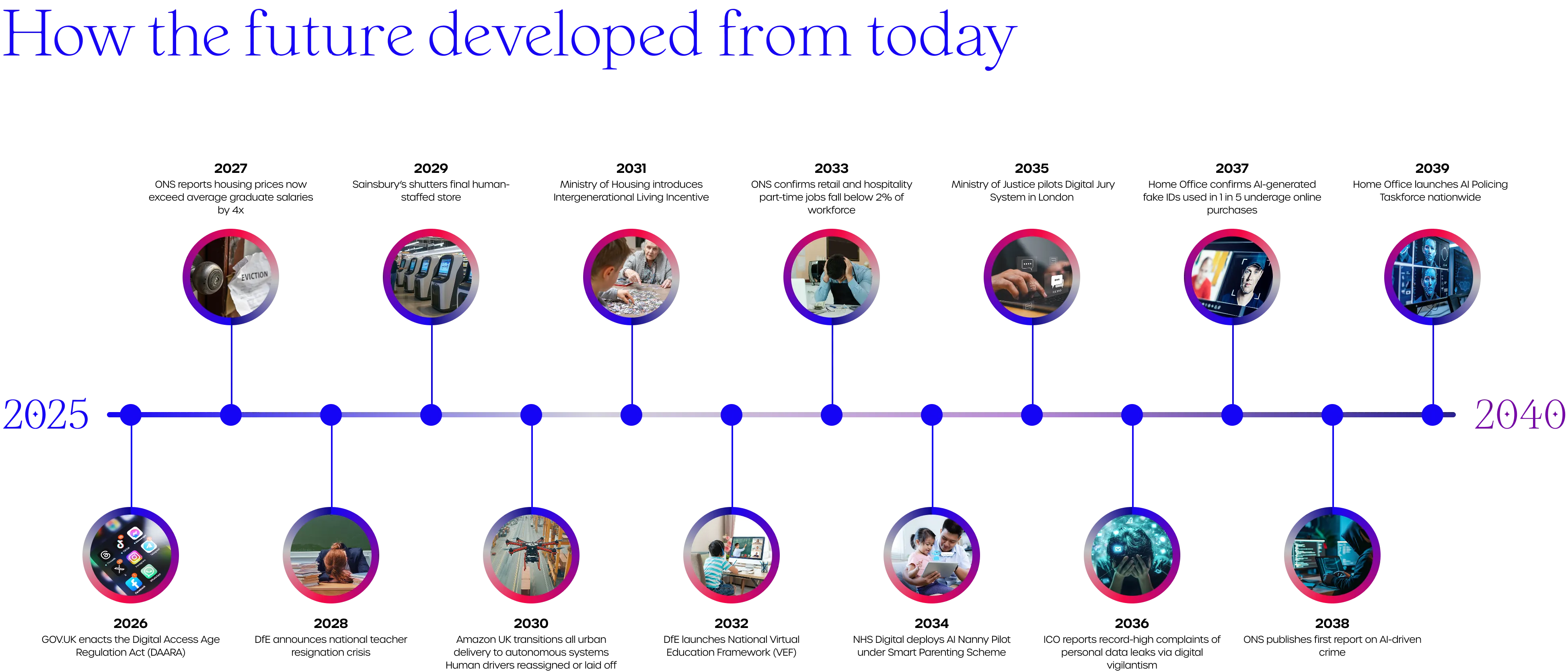

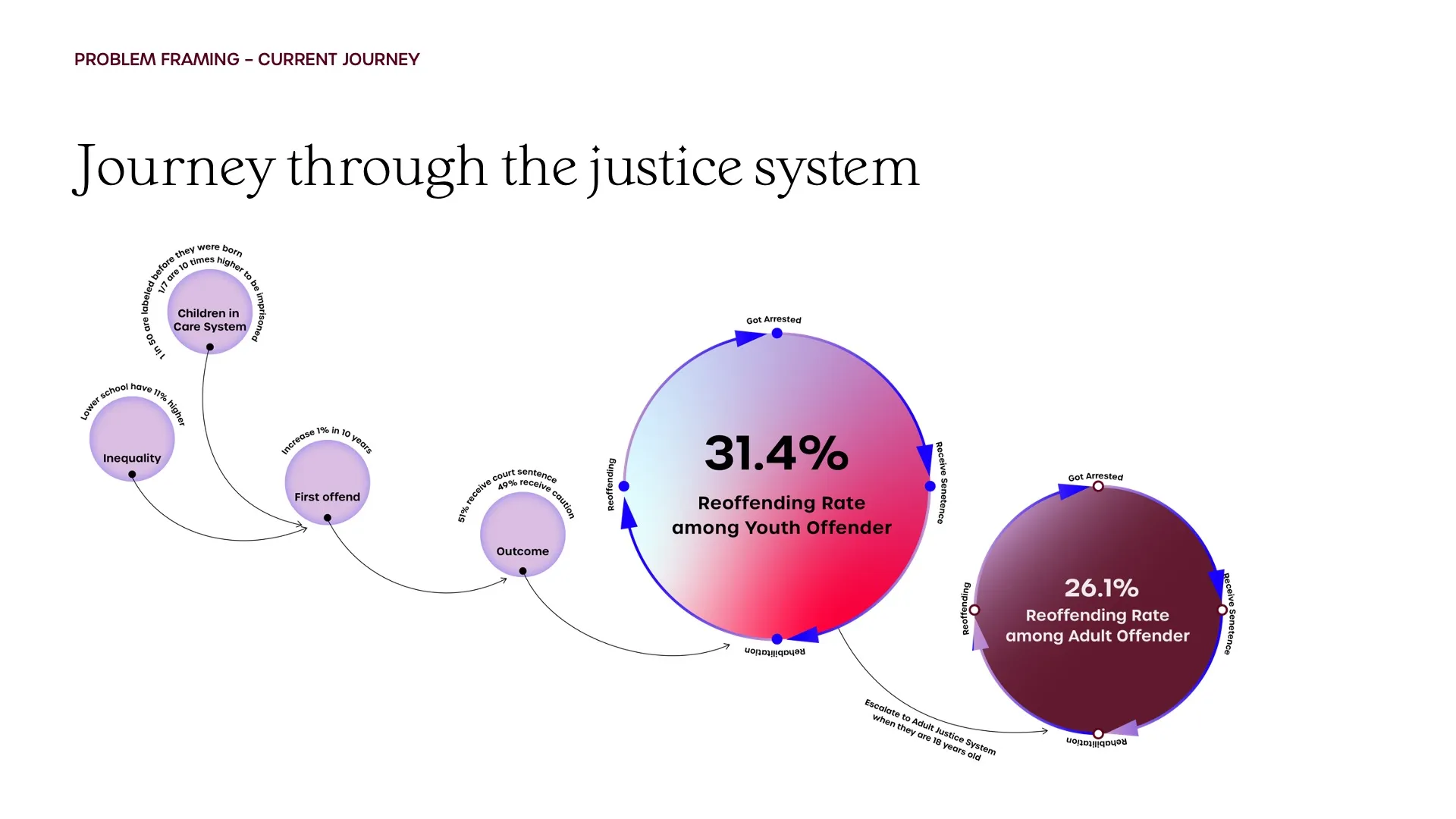

The landscape of the UK youth justice system in 2024 reflects an ongoing struggle to balance punitive measures with rehabilitative approaches. While there is a shift toward restorative justice and diversion programs, young people continue to face significant challenges within the system. Efforts to reduce the reliance on custodial sentences are ongoing, with a greater emphasis on community-based alternatives, such as education, mentorship, and social reintegration programs.

However, the system still grapples with high rates of youth incarceration, often for relatively minor offenses, contributing to overcrowding in detention facilities. This overcrowding can lead to poor conditions, lack of access to effective rehabilitation, and increased recidivism. Mental health issues, trauma, and socio-economic factors are often underlying causes of youth offending, but the system still struggles to adequately address these needs within detention centres.

For over 30 years, the UK youth justice system has seen a troubling pattern where first-time offenders who commit crimes at the age of 16 are often imprisoned by the time they reach 24. This cycle has become a harsh reality for many young people, with the system routinely opting for custodial sentences rather than rehabilitation or alternatives. Despite calls for reform, young offenders who enter the system at 16 find themselves incarcerated for years, exacerbating the very issues mental health struggles, lack of education, and socio-economic disadvantages that led them to offend in the first place.

By the time these individuals turn 24, they are often deeply entrenched in the justice system, facing the long-term consequences of early imprisonment. The lack of support, rehabilitation, and educational opportunities within detention centers leaves them ill-equipped to reintegrate into society, perpetuating a cycle of reoffending. This pattern has persisted for decades, with the system's reliance on imprisonment rather than addressing root causes remaining a consistent issue.

Several key factors contribute to the ongoing challenges within the UK youth justice system, leading to high reoffending rates and over-representation of vulnerable youth.

Firstly, educational disengagement plays a significant role, with around 11% of students from lower school backgrounds disproportionately entering the youth justice system. Many of these young people face academic struggles, truancy, and behavioral issues, often leading to their involvement in crime due to a lack of support and opportunities.

Secondly, a significant proportion of offenders come from the children in care system, where instability and trauma make young people more vulnerable to criminal behavior. The absence of a stable family environment and support network increases the likelihood of involvement in crime and eventual entry into the justice system.

The rise in first-time entrants up 1% in recent years also contributes to the issue. Factors such as family breakdowns, peer pressure, and socio-economic disadvantages push these young individuals into the system, often leading to harsher sentencing without addressing the root causes of their actions.

Lastly, the high reoffending rate of 31.4% underscores the failure of the current system. Without effective rehabilitation, mental health support, and community reintegration programs, young offenders continue to cycle through the justice system, perpetuating criminal behavior.

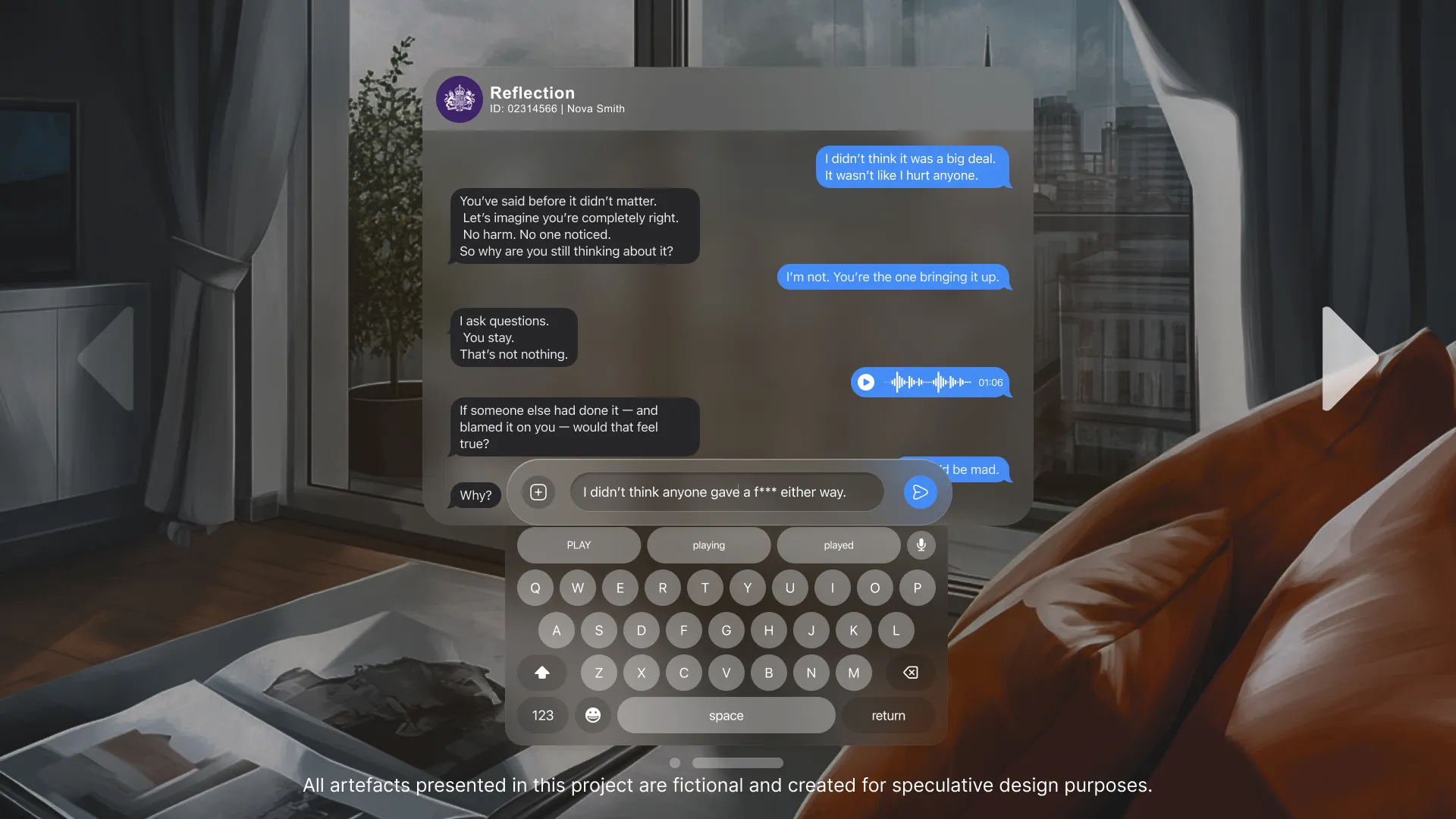

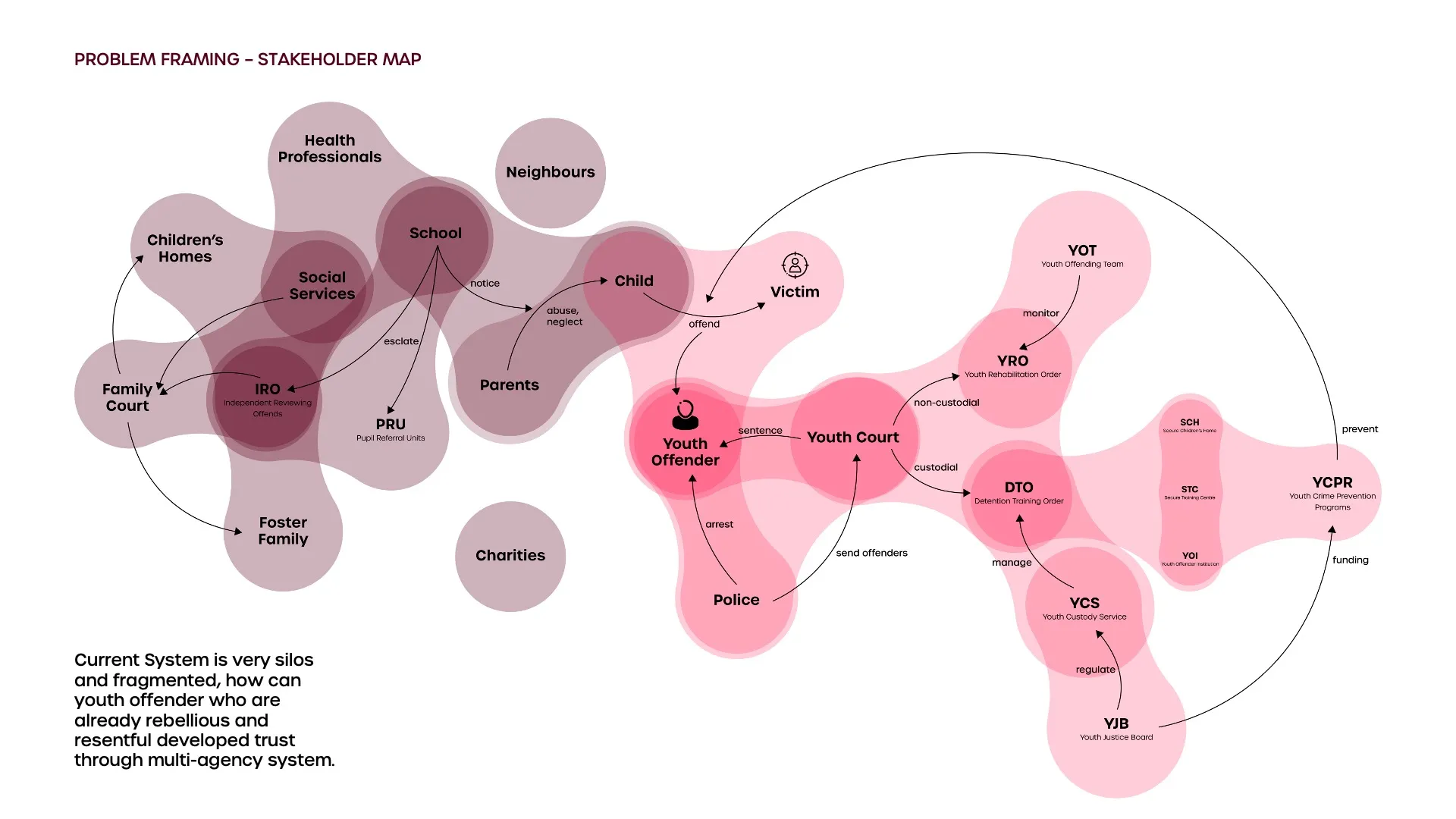

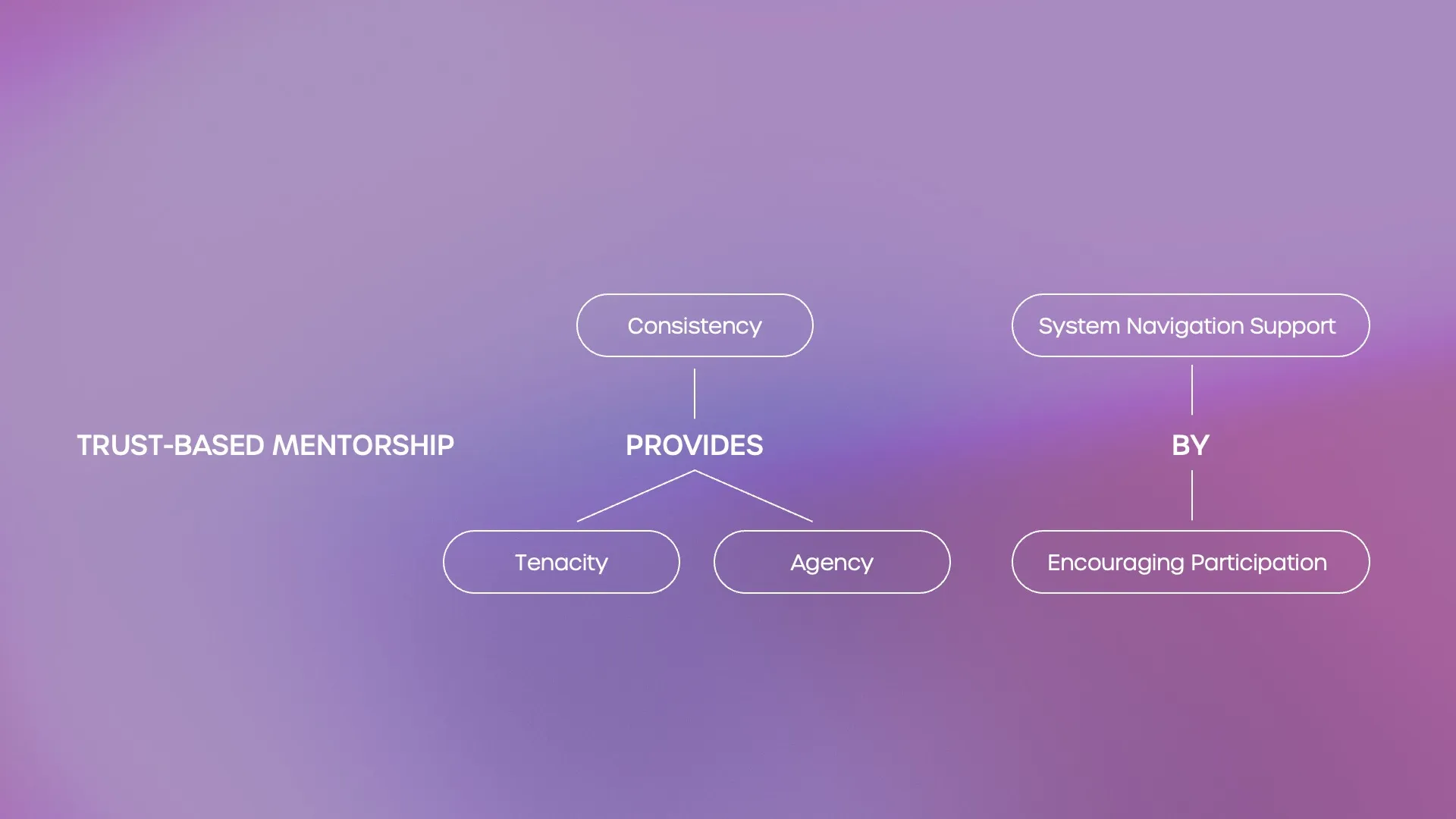

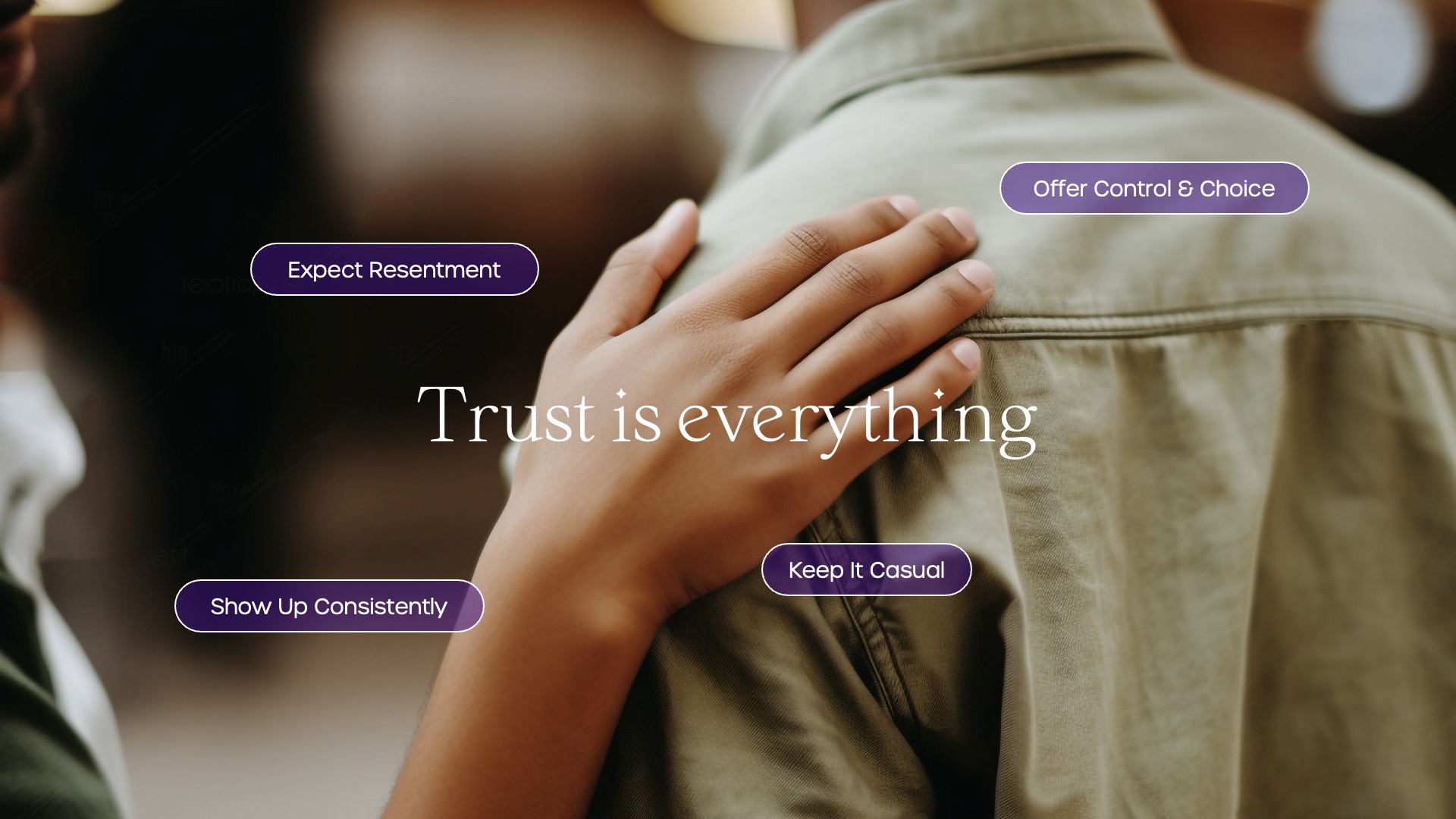

The fragmentation and siloed nature of agencies within the UK youth justice system create significant barriers to developing trust between young offenders and the institutions meant to support them. Different agencies, including social services, education, mental health services, and the justice system itself, often operate independently, leading to inconsistent support and a lack of coordinated care. This disjointed approach can cause confusion, frustration, and a sense of abandonment among young people, who may feel like they are being passed between departments without clear guidance or understanding.

For many youths, this fragmentation contributes to resentment toward the system. They may feel targeted or unfairly treated by an impersonal and bureaucratic structure, leading to a breakdown in trust. When different professionals or agencies contradict each other or fail to communicate effectively, it sends the message that their well-being is not a priority.

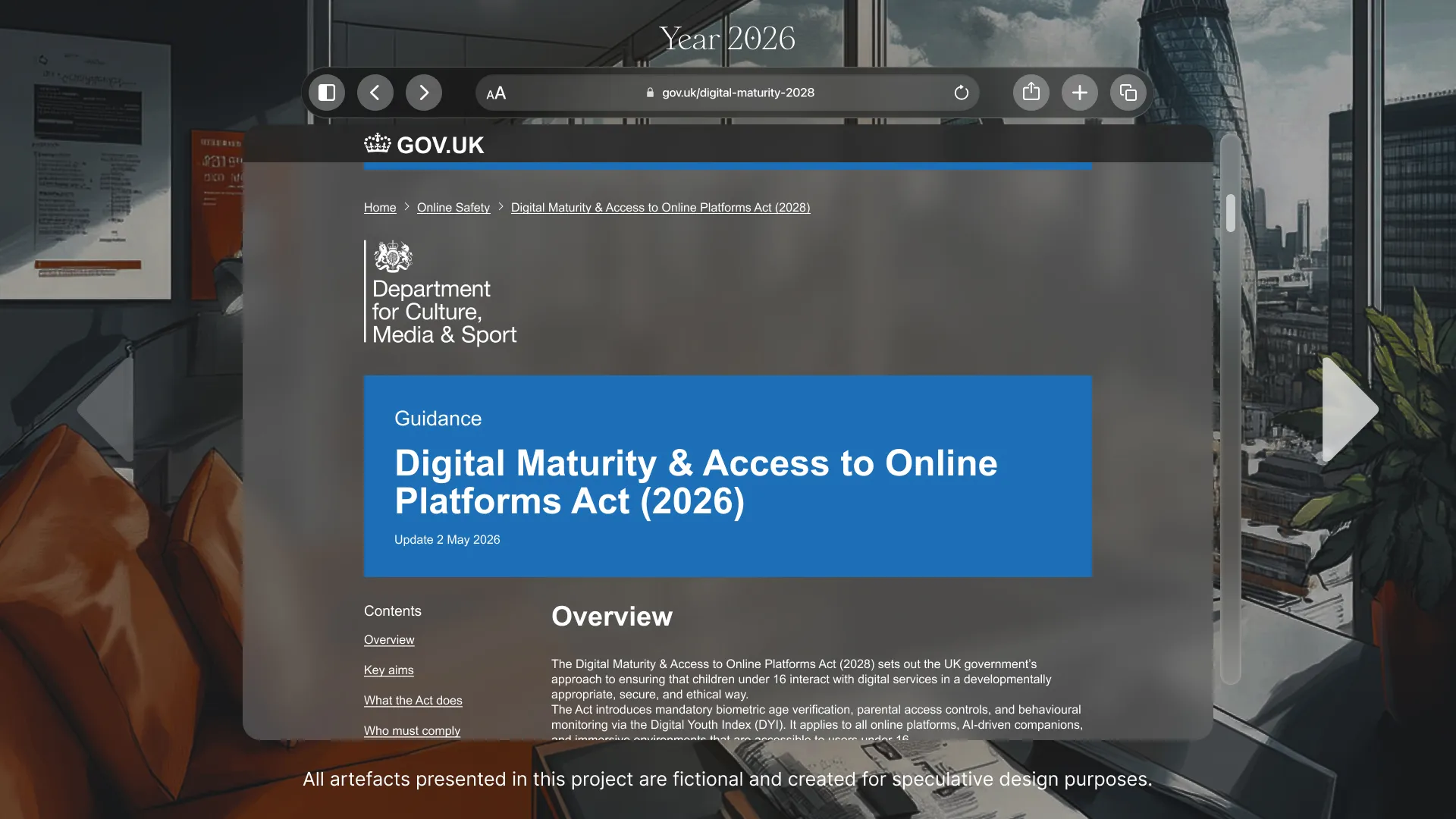

Policy Analysis

To gain a clearer understanding of how the youth justice system functions in practice, we conducted a policy analysis examining both its structural framework and operational challenges. This involved reviewing statutory guidance, government reports, and recent reforms, alongside assessing how these policies are experienced on the ground by young people and practitioners.

Our analysis highlighted that while the Youth Justice Board (YJB) sets the national strategy and oversees Youth Offending Teams (YOTs), implementation is often inconsistent across regions. Policies aimed at promoting diversion, restorative justice, and education-led interventions are present in theory, but in practice, resource constraints and fragmented agency collaboration undermine their effectiveness.

We also examined sentencing guidelines and custodial thresholds. Although policy frameworks encourage the use of custody only as a last resort, local courts frequently rely on custodial measures due to limited access to viable community alternatives. This results in a gap between policy ambition and operational reality.

Furthermore, our review of inter-agency coordination showed that policy documents consistently call for “joined-up services,” yet siloed funding streams and performance targets discourage true collaboration. This limits the ability of youth justice to address underlying issues such as mental health, trauma, and educational exclusion.

.webp)