Design sprint with London Business School's MBA Student

Year

2025

Role

Design Coach

Design at

Royal College of Art

Design For

London Business School

This case captures my experience as a design coach for London Business School (LBS) MBA students during their Design-led Innovation elective, a collaborative initiative between LBS and the Royal College of Art (RCA). The module, led by Dr. Nick de Leon, invites MBA candidates to step into the world of design, not just as a process, but as a strategic lens for innovation.

Over the course of several weeks, I supported student teams in applying core design methodologies to real-world business challenges. My role involved translating service design principles into accessible, action-oriented tools for business learners, many of whom were encountering human-centered design for the first time.

This case explores the journey, tensions, and breakthroughs that occurred when design met business, and how I navigated this intersection to foster learning, creativity, and cross-disciplinary collaboration.

As a Service Design MA student at the Royal College of Art, I was invited to coach LBS MBA teams throughout the Design-led Innovation module. While my primary responsibility was to guide the teams through the design process, I also worked alongside them in a hands-on, support role, collaborating closely during research, synthesis, and ideation.

My role included:

This dual role; part coach, part team member, allowed me to build trust, foster creativity, and help bridge the gap between business logic and design thinking.

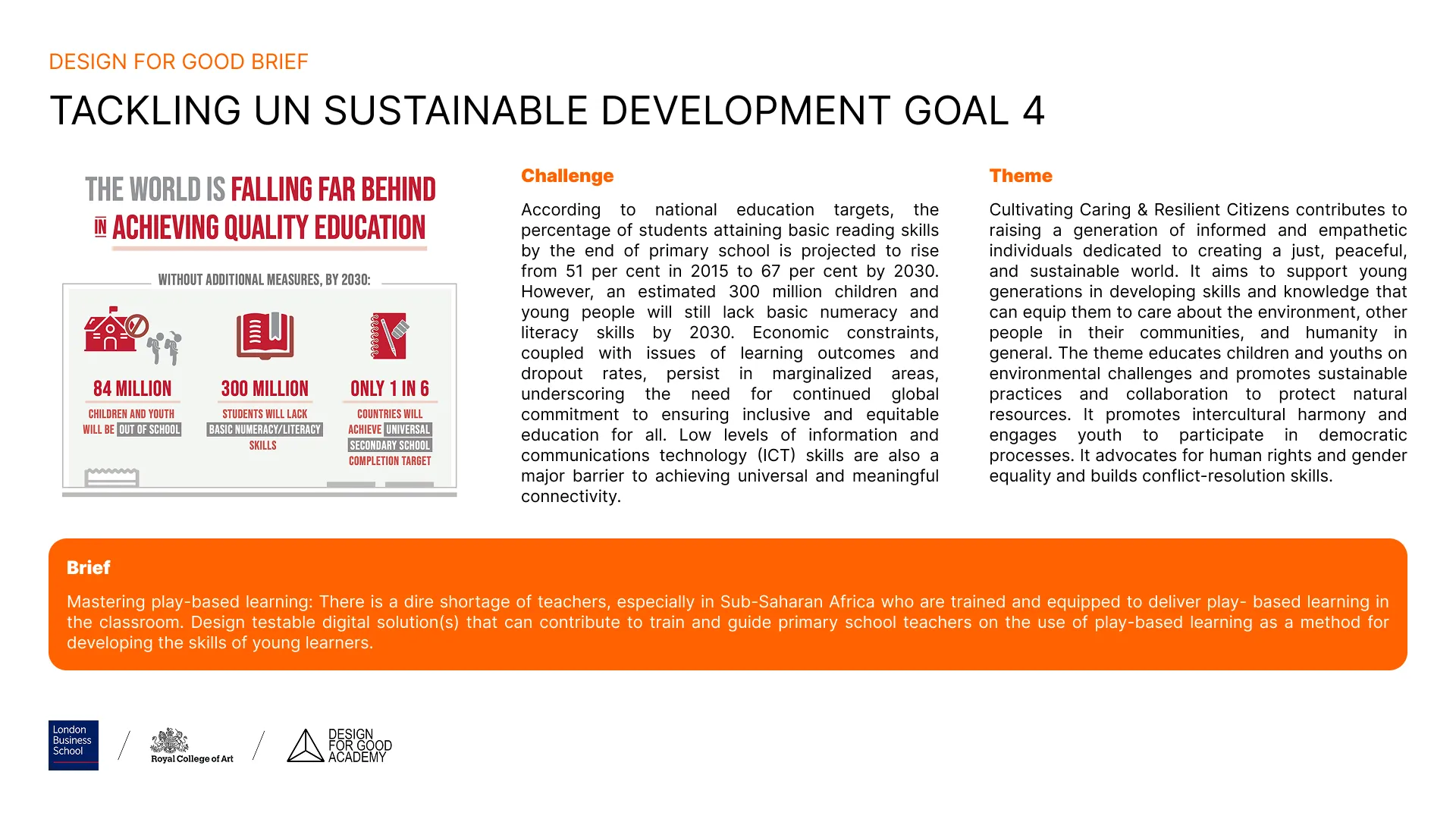

For this project, the LBS MBA team I supported chose Brief 3: Mastering Play Based Learning, developed in partnership with the UN Development Organisations and the Design for Good Alliance, as part of the effort to address UN Sustainable Development Goal 4: Quality Education.

The brief focused on the critical shortage of trained teachers, particularly in regions like Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, who are equipped to implement play based learning methods in primary education. The team’s challenge was to design a testable digital solution to support the training and guidance of primary school teachers in adopting play based pedagogy.

Our team chose to focus specifically on India, where rapid population growth, educational inequality, and teacher shortages have created urgent demand for scalable, inclusive, and locally adaptable educational tools. The solution needed to:

The brief encouraged systemic thinking—asking teams not just to design a product, but to understand the wider ecosystem

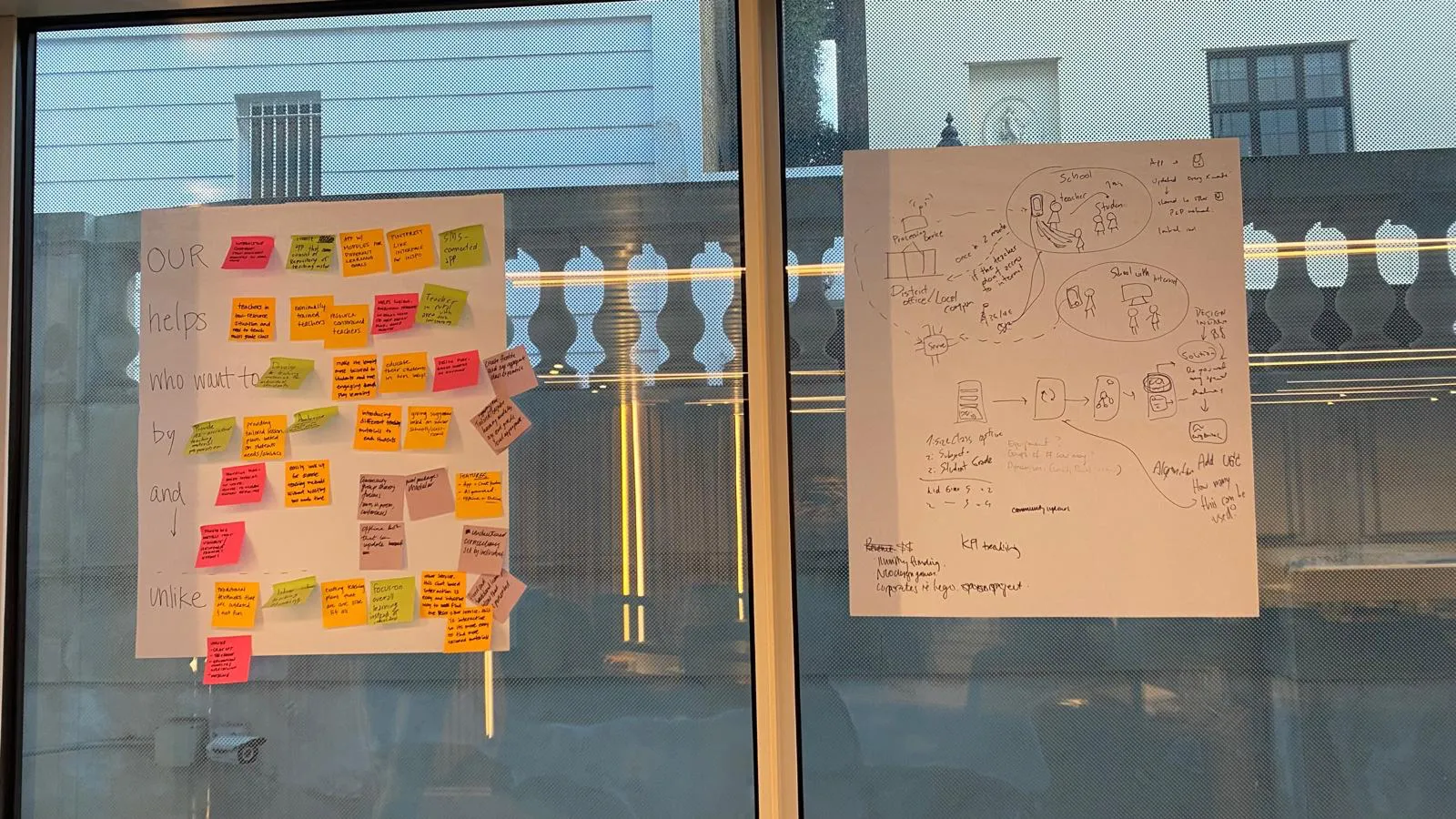

We used the Double Diamond framework to guide our design process, starting with reframing the challenge to better reflect the rural Indian education context. While the original brief addressed global teacher shortages and limited training in play based learning, our team focused on the specific barriers faced by rural primary school teachers in India, where infrastructure, pedagogical training, and access to digital tools are often limited.

At this stage, the MBA team was still thinking within a familiar strategic frame—treating teachers as end-users of a service model and education as a delivery problem. Their focus was on classroom logistics, curriculum efficiency, and formal training gaps. The questions they asked were mostly rational and operational:

This narrow framing missed the messiness of real life. It treated the challenge as a supply-side issue rather than a lived, systemic experience. As a result, their initial insights lacked emotional depth and context.

To shift their thinking, I introduced two core design tools: stakeholder mapping and journey mapping, but not in a generic way. I pushed the team to explore relationships beyond the classroom, guiding them to consider actors that indirectly shape a teacher’s behaviour, such as:

Using journey mapping, we sketched a "day in the life" of a rural teacher, highlighting not just tasks, but energy levels, stress points, and invisible labour. This reframing revealed a set of critical contributing factors:

These tools unlocked deeper insights and made the team realise that introducing play isn’t just a training problem, it’s a trust and identity problem. It’s about building confidence and shifting mindsets within a system that leaves little room for trial, error, or joy.

As the team synthesised research, their analysis leaned toward abstraction, reducing complex human behaviours into bullet points and funnel charts. There was a tendency to flatten the teacher’s experience into problems to be solved, rather than lived contexts to be understood. It became clear that without a more human lens, their insights would miss the texture and tension that design requires.

To bring depth and empathy into their synthesis, I led the team through the creation of a persona that embodied the conflicting pressures, habits, and motivations of a rural teacher—not just as a professional, but as a caregiver, neighbour, and community member. This persona became a narrative anchor, helping the team stay grounded in the real, messy constraints of everyday life.

We then worked through a structured HMW (How Might We) session, using the persona to frame opportunities that were not just functional, but emotional and cultural.

This approach helped the team stop viewing the problem as merely a lack of training or technology. They began to see it as a system of pressures, relationships, and workarounds—with the teacher navigating invisible barriers every day.

The persona didn’t just make the problem relatable. It gave the project a moral compass. Whenever a new idea emerged, we asked: Would this actually help her? Could she explain it to a friend? Would it make her feel more capable, or more overwhelmed?

By grounding abstract findings in a narrative frame, the team moved beyond user-centricity into life-centricity, designing for the person, not just their role.

The team’s first instinct was to create an app. A sleek, scalable digital solution, with gamification, dashboards, and progress tracking, felt like the obvious answer. But this logic rested on a shaky foundation: the assumption that teachers had access to smartphones, reliable internet, and digital confidence.

When we revisited our insights, it became clear this assumption didn’t hold. Many rural teachers shared phones with family members, struggled with patchy network access, or didn’t feel comfortable using apps beyond WhatsApp or voice calls. Some didn’t have phones at all.

To break that default, I prompted the team with a simple, repeated question:

“What if they don’t have internet? What if they don’t even have a phone?”

We used ecosystem mapping to visualise the broader landscape, highlighting informal communication networks, community influencers, physical spaces, and available tools. I pushed the team to see infrastructure not just as a tech layer, but as a social and material ecosystem.

We reframed design success not as what can be built, but what can be used, trusted, and shared.

This led to exploration of alternative, low-tech ideas:

Instead of launching a product, the team began building an adaptive system of access points—some digital, some physical, all designed to function in environments where tech alone would fail.

By the end of this phase, they no longer asked “How do we scale this?” but rather, “How do we make sure someone in the most remote setting can use this on Monday morning?”

As the concept matured, I shifted gears from provocation to consolidation. I prompted the team to bring all their fragmented ideas together into a cohesive solution—one that could communicate both desirability and feasibility, not just ambition.

We co-developed the core use journey: how a rural teacher, without reliable internet or digital fluency, might discover the tool, try it, and feel encouraged to continue. From there, I worked with the team to prototype key interactions that could be experienced by others; visually, physically, or narratively.

This experience was more than a coaching role, it was a live experiment in cross-disciplinary translation. Business students are trained to lead with clarity, efficiency, and confidence. But design demands comfort with ambiguity, empathy before answers, and slow thinking before fast execution.

My role was to stretch that mindset, not by rejecting business logic, but by embedding it within a richer, messier understanding of people and systems. Through tools like persona creation, stakeholder mapping, and place-based prototyping, I helped the team move from a mindset of “solution delivery” to one of “condition creation.”

I also learned how to listen for friction, not just in the work, but in the way students were reacting to it. Every moment of resistance became an opportunity to introduce a new lens, a softer question, or a more grounded perspective.

What emerged was not just a promising concept for play based learning in rural India, but a mindset shift among future leaders, one where strategy meets humility, and innovation grows from empathy outward.

This project reaffirmed that service design has a vital role not just in shaping services, but in shaping how people in power think, connect, and act.